(Best viewed with screen resolution set at 1024 x 768 pixels)

Introduction

In 2006, Martin Langley (Nicholson, 1956-61) and I were shunting an idea back and forth for a new feature article on the

Old Cambrian Website. It had to do with the Garratt steam locomotive and our memories, good and bad, of riding the school

trains that it hauled. I first saw a Garratt in the late 1940s when the old railway alignment still ran close to the Kabete

Technical and Trades School where my father taught. A friend at the school and his Dad were acquainted with one of the

engine drivers, an affable, turbaned Sikh called Mohinder Singh. Through that fortuitous connection, at the age of eight

I got a short but thrilling ride on the footplate of a Garratt locomotive from Kabete Station down to where the line

crossed the road leading to the Vet Lab. Martin Langley had also been exposed to Garratts at a tender age. He remembers

it this way: “I spent my primary school years in the South African railway junction town of Mafeking (of Boer War fame),

with many of those years living in a house close to a railway crossing. Wide-eyed, my friends and I would watch the

shunters and main line trains such as the Rhodesia Mail, headed by a Garratt, as it swung by on its way north to Bulawayo.

Later on, after moving to Kampala, I experienced the Garratt first-hand on the school train to Nairobi. These early

exposures left me with an enduring fascination with steam locomotives and the Garratt in particular.”

So Martin and I decided that someone ought to write a piece on school trains and Garratts. I had recently returned to

work full-time and couldn’t commit, but Martin bravely undertook to be the sole engineer. Thank goodness, because two

years later, after a long haul up a steep gradient, he has brought the train, loaded with treasures, into Nairobi Station

alongside Platform 1.

To read this worthy feature is to take a fascinating ride down memory lane. Its contents include schoolboy memories

(his own among them), a short history of the Garratt and the East African Railways, superb old train pictures, plenty

of notes and technical data to satisfy the railway buff, an engine driver’s personal memoir, and even a couple of sound

clips - one of them the Garratt’s distinctive two-beat chuffing, and the other a song called ‘The Good Old EAR&H’ by

acclaimed alumnus, Roger Whittaker.

All aboard, then, for a nostalgic journey back to a more innocent age when we were awestruck by the huge Garratt steam

engine (painted maroon, grey, or black depending on your vintage), and when we rode the train with such heavy hearts at

the beginning of a school term and with such great joy at the commencement of the holidays.

(Brian McIntosh, Rhodes, 1953-59)

To School Behind a Garratt

School Trains and the Locomotive That Hauled Them

The School & The Railway

The roots of the first European school in Kenya, later to become the Prince of Wales then Nairobi School, are closely

intertwined with those of the railway system in British East Africa. While the establishment of a European school in

the embryonic East African territories was inevitable, the initial impetus came from the railways. They needed a school

to educate the offspring of ex-patriates who had come out to build and operate the new railway line from Mombasa to

Uganda. The 1987 Impala reports that in 1902 the Uganda Railway Authority established the European Nairobi School,

located in the current grounds of the Nairobi Railway Club. In 1916 the school was moved to the hilly grounds of

Protectorate Road, currently the Nairobi Primary School. Then, in 1925, at the urging of Lord Delamere and supported

by the governor of Kenya, Sir Edward Grigg, planning was initiated for a new boys secondary school to be run on the

lines of an English public school. The location chosen for the new school was on railway reserve ground near Kabete

(ref 2002 Impala). Thus the Prince of Wales School came into being in 1931.

The school has always enjoyed a close relationship with the railway. There were visits to the railway workshops,

organized by school societies, such as the Scientific Society (Dec 1953 Impala). The Dec 1949 Impala reports that

“Mr.J.Collier-Wright and two of his colleagues, gave us much information about careers in the EAR&H”. Sport also

figured prominently in relations with the EAR. Probably the school’s oldest competitor in sports (in colonial times)

was the Railway Club, a perennial rival in sporting fixtures particularly in hockey, rugby, cricket and soccer.

A few alumni who have registered on the OC website reminisced on the days when the railway line passed close to the

school on its way between Kabete and Nakuru. They relate how coins were placed on the rails to be flattened and

collected for later admiration. Grease or butter was applied to the rails and the resulting slipping of the giant

wheels of the locomotives no doubt watched with great glee from the concealment of nearby bushes. The June 1952

Impala under “Hawke House notes”, speaks of this practice when looking back to 1942. The article remarks “On one

or two occasions, they sallied forth at night to grease the railway line and then to watch the train vainly trying

to mount the grade”.

b

d

As noted by Christopher Collier-Wright (Hawke 1954-1959), “The original line between Nairobi and Nakuru ran by the

north side of the Prince of Wales School on its way up to Kabete. The gradient in the vicinity of the school, as

in some other sections of the line, was 1 in 50 (2%). This meant that while at the beginning of the term the ‘down’

train bearing pupils from up-country and Uganda could stop to drop them and their luggage on the perimeter of the school,

at the end of term the boys boarded at Nairobi station. The general area where the train stopped would have been just

north of the hedge, beyond the school hall/swimming pool, outside the school compound. If the ‘up’ train stopped by the

school, it would have great

difficulty in getting started again. Mervyn Hill in his magisterial work ‘Permanent Way: The Story of the Kenya and

Uganda Railway’ writes ‘Work on the Nairobi-Nakuru realignment, which had been held up during the war, and which was

designed to reduce the 2 per cent grades to 1.18 and 1.5 percent, against up and down traffic respectively, was

resumed’ (in 1946). The new route which passed by Kibera was opened in about 1948, no doubt to the relief of engine

drivers whose locomotives had been known to be brought to a halt as a result of grease spread on the line by recalcitrant

schoolboys. True, the new alignment passed the Duke of York School, but its gentler gradient meant that any Yorkists

who tried to play the same trick were likely to be unsuccessful.”

Above - Kenya & Uganda Railways 52 Class Garratt passing the Prince of Wales

School – 1936

Above - Kenya & Uganda Railways 52 Class Garratt passing the Prince of Wales

School – 1936

Photo supplied by Oliver Keeble

Left - Offloading Boys' baggage from the train, Jan 1931.

Photo supplied by Cynthia McCrae (née Astley) and Alastair McCrae (Rhodes 1943-1946). - originating from the photo

albums of Bernard Astley (Headmaster 1937-1945)

Many Old Cambrians still remember those days, when the railway line ran past the school.

John Cook (Hawke/Nicholson 1941-45) relates how love stopped a train.

A Passing Kiss 1

It was 1944. The world was at war but at Kabete, a few miles north-west of Nairobi, the Prince of Wales

boys boarding school was a bastion of peace and contented learning.

The extensive grounds, dominated by the classic structure of the Herbert Baker designed buildings covered

many acres of land. On the north-eastern boundary and just over the school fence ran the main line of the East African

railway – the metre gauge track that ran from Mombasa to Kampala.

It was this railway and its trains that many of us boarders depended on to make our way back at the end

of term to our homes in Naivasha, Nakuru, Eldoret, Kitale and many other towns along the way.

Nearer to Nairobi and quite close to Government House stood another school – The Nairobi Girls High

known by us lads as the “Heifer Boma” where many of us had girl friends.

It had been normal for both schools to break up at the same time and pupils to share the train that took them home for the “hols”. But in December of the previous year the railway authorities reported to the respective principals that a good deal of bad and unruly behaviour had occurred on the pre-Christmas journey home. This led to a decision that the girls would be sent home two days earlier than the boys at the end of the term.

The lads were devastated by the news but a bunch of about a dozen of us hatched a plan that would allow a swift but amorous rendezvous.

The rail line alongside the school was noted for its steep elevation and even the biggest and strongest Garratt steam engines struggled up the sloping line.

For the ten days prior to the day on which the girls were due to pass by, the team endured dry bread with lunch and dinner smuggling our butter rations out of the dining room and storing them in our leader’s locker.

On the day in question the train carrying the girls was due to pass the school at 4.15 pm at a time when formal classes were finished and sport about to begin. At 4 o’clock the lads rushed across to and over the fence on the boundary and smeared their hard won butter ration on about 30 metres of both rails. Hearing the approaching locomotive they dived into cover in the bushes along side the rail and waited.

The train was making heavy weather of the steep gradient and no sooner did it reach the buttered section than the main drive wheels of the engine started to spin as the driver applied increased steam pressure and the train came to a steaming, wheel-spinning halt.

But the turbaned Sikh was prepared for such an event. Quite often in the past early morning rime on the rails in the highlands had caused this skidding event and the answer was to spread sand along the affected line to provide grip for the spinning wheels. He descended from the cabin with a bucket of sand and started providing a cure for the problem.

Meanwhile from every window of the train passenger heads peered out, curious as to the reason for this unscheduled stop. The fifth carriage from the engine was particularly noticeable for the large number of young female heads that appeared at the open windows.

No sooner had the driver – now joined by the guard – gone to the far side of the locomotive to apply sand to the track than our group of eager young men broke cover and boarded the coach to the screaming delight of the young ladies.

The couples had so little time. Lots of hugs and snuggles. Exchanges of small tokens of love and then the sound of increased steam activity as the driver began to get the train under way.

One final kiss to each of their beloved and the daring dozen leapt from the carriage – standing beside the embankment to wave a fond, but sad, farewell to their sweethearts.

Giving up our butter ration sure was worth a passing kiss.

b

d

John Cook’s romantic adventure is confirmed by the self confessed involvement of Redvers Duffy. Could it have been the

same train as John’s?

Redvers Noel Duffy (Clive 1942-47)

I was involved in the ambushing of the girls high school train at the end of one term which resulted in the train

being brought to a standstill due to the fact that the rails had been greased and the train was unable to attain

enough traction to traverse the gradient past the school. The greaser of the line was the only one suspended because

of his actions, but his identity is better left unspoken. I was one of many who escaped punishment for that little

escapade.

Ray Birch (Hawke/Grigg 1942-46) remembers

Initiation ceremonies which included the dreaded slide, pushing a coin along the railway line with one's nose,

the pill made up of unmentionable ingredients and swallowed by newcomers, duckings, disembarking from the train

from Uganda which stopped outside the school to disgorge pupils from Uganda and points en route, greasing said

railway lines, waiting for steam engines heading upcountry from Nairobi to lose traction on the gradient and

wheels spin uncontrollably (this was a caning offence I think but great fun), putting 10 cent coins (they had a

hole in the center) and retrieving the flattened object after it had been run over by the train. At the time,

the Kenya/Uganda railway line passed through Nairobi via the DC's office and up past the school. It was later

of course re-routed to its present location.

Ron Bullock (Scott 1948-53)

It was during my first term that we heard dark rumours of two senior boys getting six from Flakey and then being

expelled for having held up the train. I was never able to verify the details, but perhaps someone can at this

late date shed some light on the mystery. It seems they had greased the line with butter, which caused the Uganda

mail to grind to a halt on what I believe was the steepest rail gradient not only in Kenya, but in the empire (1:52

if I remember correctly). Even when they got the rails cleaned up, it seems the train had to reverse back into Nairobi

station to get a good run at the hill - 36 hours late, I heard. And whilst talking about the old alignment, the

up-country types will probably remember how the down train used to stop outside school to let us off, and how

miserably we dragged our bags or trunks up the hill to our respective houses.

Tom Palmer (New House 1948-51)

I also remember the incident where all the guys scraped the butter from their bread, collected it and then spread it on

the Railway line, which in those days passed the Prince of Wales School. This caused no end of problems for the train

which had to reverse all the way back to Nairobi. This happened several times before the reason was discovered. Severe

reprimand for the School by "Flakey" the Headmaster. The train always had great difficulty climbing up to the escarpment.

Robin Hoddinott (Nicholson 1948-52)

I used to take the train to school from either Turi or Elburgon, and at least for the first few years, the train used

to go right by the school. At the beginning of each term, it would stop at the school to let us students off so the

school wouldn't have to send the bus to Nairobi station. Some of the masters and other staff were always there to welcome

us back and help pack our luggage back to our respective houses. On one memorable occasion I recall, someone forgot to

tell the train engineer to stop, and much to our joy, the train rumbled right on by while the school staff stood by

waving frantically. Our joy was short-lived, though. When we arrived at Nairobi station, the school bus was already

there waiting for us. At the end of term, we always had to go to Nairobi to embark. I guess the grade beside the

school was too much for the old Garratts to get the train started again if it stopped, (there was a story that someone

was expelled once for greasing the tracks) or maybe it was just the logistics of getting our tickets and assigning us

to specific compartments. If I remember correctly, the train used to be split at Nakuru, one part carrying on to Kisumu,

while the other went to Kitale. The ride home was always a joyous occasion. We usually hoped to be assigned to one of

the older carriages that didn't have the corridor running down one side. A favourite trick was to hold a roll of toilet

paper out the window and let it unravel so that the train arrived at the next station festooned with streamers of paper.

In the older coaches, none of the train staff were able to get to us to prevent this. On another occasion, on the way to

school, my hat blew out the window just as we were pulling in to Longonot station. When the train came to a stop,

I jumped out and ran back to retrieve it, but only just made it back to the guards van before the train took off again

and I had to ride to the next station (Kijabe) with the guards. So, as you can see, Roger Whittaker's song about "The

good old EAR & H" brings back memories!

b

d

While the majority of train commuters were from Uganda or upcountry Kenya, many came from Tanganyika, with the

journey from the furthest reaches of that country taking nearly four days. Some lads from Uganda and Tanganyika

remember their journeys to school.

b

d

John Nicholson (Scott 1948-53)

My father worked in Uganda so I was a boarder and travelled to school by train. Most of the boys from Uganda got on

the train at Kampala but myself and J J Woods (Hawke) and his younger brother didn’t get on until Tororo. The Kampala

boys included John Williams (Scott), Jim Watson (Scott), Peter Overton (Scott) and George ‘Squeaky’ Mowat (Grigg).

In the early days before the rail track was re-routed it used to pass by the school before getting to Nairobi station

so the train used to stop opposite the school to let us off. The journey in those days from Nairobi to Nakuru was not

all that speedy. I say that because in my latter trips home a friend and myself used to jump train at the first suitable

stop after leaving Nairobi and hitchhike to Nakuru to pick it up again. The train journey took about 6 or 7 hours and

having done the trip so many times before we were often bored and alternative travel was a lot more interesting. We

always reckoned to have plenty of time and once on the road the first vehicle that came along always stopped to offer

a lift, in fact we were so early in Nakuru on one occassion that we had time to see part of a film show at the local

cinema !

Paul Heim (Hawke/Scott 1946-50)

For many of us, the introduction to the School started with the journey from our homes. In my case, it was by train from

Tabora (in Tanzania), to Mwanza on Lake Victoria, where one spent a day, usually at the Club, waiting for the lake steamer.

The club had facilities for swimming in the lake, by way of an old anti-submarine net, intended to keep out the crocodiles.

Nobody seemed to think it necessary to point out that a net which would keep out a submarine was not necessarily a

deterrent to a croc. If the steamer went clock-wise round the Lake one would go to places like Bukoba, the far end

of the world, on the west side, before going on round past Uganda to Kisumu, and if one was lucky, it went anticlockwise,

which only took a day and a night. One then disembarked at Kisumu, and had to wait for the next train, which usually came

on the same day. Again, we would try to find something to do. On occasions, we jumped over the fence into the Kisumu Club,

to use their pool. The train took a night and a day to get to Nairobi, but by then numbers of other boys had joined the

train, and the journey was fairly eventful, especially for new boys. Bullying started at that moment. The train did not go

very fast. It was possible to get off it, run alongside, and get on again. It was also possible to get on the roof of one’s

carriage and jump from one carriage to the other, all the way along the train.

The train stopped near the school grounds, to allow the boys to disembark, and to stagger up to the school, each

carrying the vast regulation tin trunk, usually, in true African fashion, on his head.

Stuart Thomas (Clive 1952-56)

I also remember, one of the boarders from Tanganyika, got themselves into serious trouble on the train coming to school,

I think. May have had something to do with a young African girl, my memory is not that good, so I had better be careful.

Anyhow, as soon as he arrived at School, he went straight to "Flakey's" office & was expelled on the spot, & given you

know what, just to rub salt into his stupid wounds. I can only add to that by saying, he must have deserved it, because

I believe that our Headmaster was a gem of a man overall, the same as our Housemaster Mr.Fyfe.

Edward David (Clive 1952-56)

It took us 4 days to get to school - leaving Dar-es-Salaam on Monday evening @ 10 p.m. traveling by train/bus/train to

arrive in Nairobi on Thursday morning!!! I remember it well!!! Years later we would fly on EAAC DC3’s -

Nairobi-Mombasa-Tanga-Zanzibar- and finally arrive in what a wonderful place - Dar-es-Salaam in about 4 hours!!!!

Jeremy Whitehead (Clive 1958-62) with a humorous incident on the Uganda train.

I can recall attending the first assembly of a new term and listening to the headmaster, Fletcher, lecturing us on

appalling behaviour on the school train to Uganda at the end of the previous term. He was unwise enough to describe one

particular event when a group of us had set upon a St Mary's boy and hung him out of the train window by his feet,

whereupon the whole school erupted in a great gale of laughter bringing the lecture to an end as he was unable to

prevent himself joining in the laughter.

Jeremy also travelled from Kasese in Western Uganda to Nairobi a number of times and he relates an incident on the

way to school when the rear end of the train became derailed. He continues – ‘the problem was resolved after a couple

of hours by uncoupling the derailed Third Class portion and employing the Third Class passengers to convey the First

and Second Class baggage (including my bicycle) to the freight car at the front end. This was done with a good deal of

laughter and cheering. The Journey was then resumed leaving the Third Class passengers and derailed carriages to be

rescued later’. (Jeremy discovered to his sorrow that the Kasese-Kampala line is no longer operational as are many

segments of the original EAR&H network)

b

d

Trains were very much a feature of school life for those that used them, signaling as they did the beginning or end of a

term or year, each trip a segue between the disciplined environment of school and the warm bosom of home or vice versa.

The lightly supervised school train usually gave way to mischief that only teenage boys away from home or school can get

up to; smoking, girls, rugby songs, practical jokes, initiations etc.

b

d

In this colourful account of his journey to school from upcountry Kenya, Stan Bleazard provides a lyric description

of an arriving Garratt, and his initiation as a rabble.

Stan Bleazard (Grigg/Rhodes/Scott 1945-48)

Two dim oil lamps glowed faintly in the mist at each end of the railway platform at Maji Mazuri station. In total

darkness between them, I sat quietly waiting on my battered tin trunk. It was cold and I began to shiver. There was

no sound, not even a dog barking in the sawmill's labour lines across the valley. Absent also, the occasional scream

of a hyrax from nearby forest, with which I always associated home. Just the customary brooding silence that can

sometimes pervade a long African night. The minutes hung, leaving nothing to record their passage, until my guardian

audibly rummaged his coat pockets. A match flared as he lit a cigarette. Without interest, I watched it glow each time

he sucked in the smoke he craved. When he finished, he sent the end tumbling away onto rail ballast, where briefly it

continued to glow.

The familiar tinkling of bells, coming from the control desk in the station office, told us the train was on its way.

After about ten minutes, the steam locomotive's bright headlight bored through the mist briefly as it emerged from a

cutting in the distance toward Equator station several miles away. Shortly after, I heard the Sikh station master step

from his office, his chaplis shuffling in the cinders of the platform's surface. I felt sure he would be carrying a metal

hoop that he would somehow, without seeing properly, exchange with one brought by the loco's driver.

Faint at first, then strongly from just beyond station limits, the Garratt's siren blasted warning of its imminent

arrival. The mist that way began to visibly brighten. Turning into the final straight, the loco's beam suddenly exposed

the three of us in brilliant light. Blinking, we turned away in response. Underfoot, I distinctly felt the ground shake

as the juggernaut approached and rushed past. The moment darkness resumed a blast of heat from the loco's firebox hit us.

The screech of iron shoes grinding against steel wheels jarred my teeth as the driver applied brakes to every carriage.

Finally the train stopped with a shudder. The Ticket Examiner flashed his torch at us to show me to my reservation.

As usual, at 0300 hours I was the only person to board.

Struggling to shove my trunk through the entrance doorway, I twisted my thumb on its beastly metal handle. Most

compartments were still lit, so it was easy to find mine. Entering, I greeted two glum looking young fellows who only

grunted a response. The Garratt's siren sounded and we were soon moving. I was hardly settled when shouts of 'Rabble'

emanated from somewhere at the end of the corridor. Such address was of course unusual and, ignorant of its meaning I

at first ignored it. I felt people were rude making such a lot of noise at this hour. Not many seconds elapsed, however,

before I was forcibly seized by a couple of ruffians, manhandled to the far compartment and persuaded to introduce myself

to several other aspiring thugs. The air inside was full of smoke and it stank of beer. From their intense questioning,

I was soon aware that they wished to find grounds for unfair criticism, or any reason at all to mindlessly berate me.

Much of this was demeaning, especially aspersions about my heredity. Having exhausted their verbal assault on me, they

then demanded I sing for their entertainment. Not well gifted with this facility, my various attempts brought only

displeasure, which brought on physical abuse to encourage me to perform better. What followed need not be recorded in

detail. Fortunately my vilification did not last because more pupils boarded at Sabatia, the next station. With my

tormentor's attention momentarily diverted, I escaped and made as fast as I could to the furthest end of the train. I

spent the next hours until daybreak squatting with difficulty in an oriental style toilet. That was how the journey for

my secondary education began, which turned out by comparison to have been typical experience for most of us.

Brod Purdy (Rhodes 1958-62) travelled from Kitale, joining the Uganda train at Eldoret.

With a schoolmaster as a father, it was rare that I had to use trains initially as we lived in Embu. However there was

one journey that, for some reason, always sticks in my mind. The nearest railhead to Embu was Sagana, and it was at this

out of the way halt that I embarked on my first school train journey. As a new boy, fresh from a minor English Public

School, I was frequently the butt of those who had been at the PoWS for a much longer time than I. And so it transpired

on this particular trip where, although not hung out of the window of a carriage, I was summoned to a senior’s compartment

and put through a rigorous ‘Third Degree’. I eventually escaped, but with a crushed fingertip…those EAR&H doors were

brutally heavy.

Some years later with the appointment of my father as the Headmaster of the African Secondary School at Kapenguria which

some may remember as the school at which Jomo Kenyatta was famously tried, my school journeys now started and finished at

Kitale. We would all embark at Kitale and head to Eldoret where the train would wait for the Kampala train to

join…figuratively and literally…us. We would arrive in the late evening and be shunted into a distant siding, supposedly

out of the way of temptation. How wrong people were. Most of us would manage to exit the carriages tucked away and

cross the tracks and head for the bars of Eldoret where the following term’s pocket money was spent. And then we would

attempt to return to our train before the Kampala train arrived. This was not normally a problem, until the occasion

when the authorities decided to move our train to a different part of the station. Imagine a crowd of PoWS and DoYS

lads trying to find a train in the dark and hoping that it was not already on its way to Nairobi…without us!

And then I became a prefect and had my own compartment and rabble to do my every wish. However, this arrangement did

not have the blessing of EAR&H and I remember being woken in the early hours of the morning to find a rabble sharing my

compartment…and the look on his face when he woke up to find he was sharing a compartment with the prefect that had

soundly thrashed him the term before for some misdemeanour or other.

And the journey when some rabble lost my hockey stick and I had to spend the rest of the term using those supplied by

the House.

For some reason I seemed always to return home after everyone else, but memories of dinner (with wine) coming down the

escarpment before pulling into Naivasha…and then the overnight stop in Eldoret before continuing to Kitale when I was

caught sneaking into Eldoret by, of all people, my father who had driven down from Kapenguria to pick me up. Without

telling me.

b

d

As Stan Bleazard recounts in his story, schoolboy commuters typically boarded the train bearing a battered old

galvanized metal cabin trunk, a scuffed veteran of numerous trips, that was made by some fundi in the town they

lived in. The trunk had a welded hasp and staple wherein a padlock could be inserted, and two flip handles on

the ends and another where the hasp and staple were. In this trunk would be all the boy’s clothes, shoes and “stuff”

for the coming term. During term, it would be kept under the boy’s bed in the dormitory.

As Stan Bleazard recounts in his story, schoolboy commuters typically boarded the train bearing a battered old

galvanized metal cabin trunk, a scuffed veteran of numerous trips, that was made by some fundi in the town they

lived in. The trunk had a welded hasp and staple wherein a padlock could be inserted, and two flip handles on

the ends and another where the hasp and staple were. In this trunk would be all the boy’s clothes, shoes and “stuff”

for the coming term. During term, it would be kept under the boy’s bed in the dormitory.

The author had an unnerving experience with his trunk. Once, at the end of term, while still a rabble, a senior

shoved him into the trunk, latched the hasp and heaved the thus occupied trunk into a bathtub full of water in the

Nicholson House bathroom. And there it floated, the occupant in claustrophobic darkness with water slowly seeping

in and filling the interior, while he screamed his lungs out in abject terror. Unable to open the thing because it was

latched, he thought he was dead, drowned like a rat in a drain. Finally, after what seemed like an eternity, the lid was

opened by the still guffawing tormentor and the prisoner was released, trembling like a leaf. Denis M, I'll get you,

you bastard!! (....grin).

b

d

A Career in the Railways

A career in East African Railways was a respected vocation for many Old Cambrians. Some entered into the Railway Training

Workshops as apprentices in railway maintenance or operations. In addition to trade apprenticeships, others completed

University degrees and jointed EAR&H as cadet engineers or commercial management trainees. Mick Houareau and Gerry Beers

both had careers with the EAR and their stories follow.

Michael (Mick) Houareau (Clive 1953-56)

Left - EAR apprentices in 1958 – Mick is nearest the locomotive

Left - EAR apprentices in 1958 – Mick is nearest the locomotive

After school, I joined the East African Railways as a mechanical engineering apprentice. I did time in the various

shops including the machine, loco fitting, erecting shop, loco wheel shop, Westinghouse brake shop, foundry, drawing

office and copper shop. The apprenticeship was interrupted by National Service in the Kenya Regiment. After doing

time in the various shops I was put back in the loco erecting shop where I completed my time. The erecting shop was

where all the locos from the smallest 10 class shunter to the largest Beyer Garratt 59 class were completely overhauled.

On completion of each overhaul, the locos were taken on a short test run , usually to Athi river.

Another Old Cambrian apprentice during my time there was Paul Newman (Rhodes 1950-54) who later was to work on the

diesel side while I stayed with steam.

Gerry Beers (Hawke 1948-52) reminisces on his career with the EAR&H

I joined the EAR&H as a Cadet Engineer in 1957 after I got a degree in Civil Engineering from Trinity College, Dublin.

While I remember

the Garratt locomotives well – particularly the mighty 59 Class - from my short time in Nairobi, I spent most of my

time on new construction in Tanganyika. My first job was the construction of a new dhow jetty in Dar es Salaam and then I worked on the Kilosa to Mikumi spur, which

we fondly thought would be the start of the link with Rhodesia and then South Africa. It was, of course, made redundant

when the Chinese built the line from Dar which still operates – just! I was also responsible for a time for the

maintenance of about 100 miles of the Central Line from Dar.

I finished as 'Engineer in Charge' of the southern half of the Ruvu – Mnusi link (see map left) between the Central and the Tanga lines

but at no time did I ever work with Garratt locos. To the best of my knowledge they never worked in Tanganyika – we

were the poor relation. (There were in fact Garratts in Tanaganyika –Ed)

I finished as 'Engineer in Charge' of the southern half of the Ruvu – Mnusi link (see map left) between the Central and the Tanga lines

but at no time did I ever work with Garratt locos. To the best of my knowledge they never worked in Tanganyika – we

were the poor relation. (There were in fact Garratts in Tanaganyika –Ed)

Reflecting on those far off days I remembered a couple of incidents which were quite nice. After we finished the dhow

jetty in Dar es Salaam (1958) I was in the New Africa hotel (not unusual!) when three old wizened Arabs approached me

and insisted on buying me a beer. They said that their life was much better now that they could load and off-load their

dhows at both high and low tide and were very grateful. Another example of how the EAR&H was appreciated occurred when

we were building the Ruvu – Mnyusi link. Every day an engineering train took 500 tons of ballast to the railhead and

returned empty. We allowed any of the locals to ride back on the return journey and of course didn’t charge them.

One day an old African farmer came up to me in the bush and told me how much his life had improved because he could

now get his bananas to market in one day instead of three. I like those two memories.

b

d

Thus was forged a strong link between the school and the railways. From the very beginning that same railway, over

the years, was to ferry thousands of schoolboys (and girls) to and from school, from the furthest corners of East

Africa. To school they came, riding the train/bus for up to 4 days, from Dodoma, Arusha and Dar-es-Salaam and from

the southern shores of Lake Victoria in Tanganyika, from Mombasa’s white sands, from Kisumu, Eldoret, Thomsons Falls,

Nakuru and other points in the upcountry farmlands of Kenya, from the mining town of Kasese in the foothills of the

Ruwenzoris and from Kampala, capital of verdant tropical Uganda. One of those commuters was Roger Whittaker who

wrote a song about riding the old school trains.

b

d

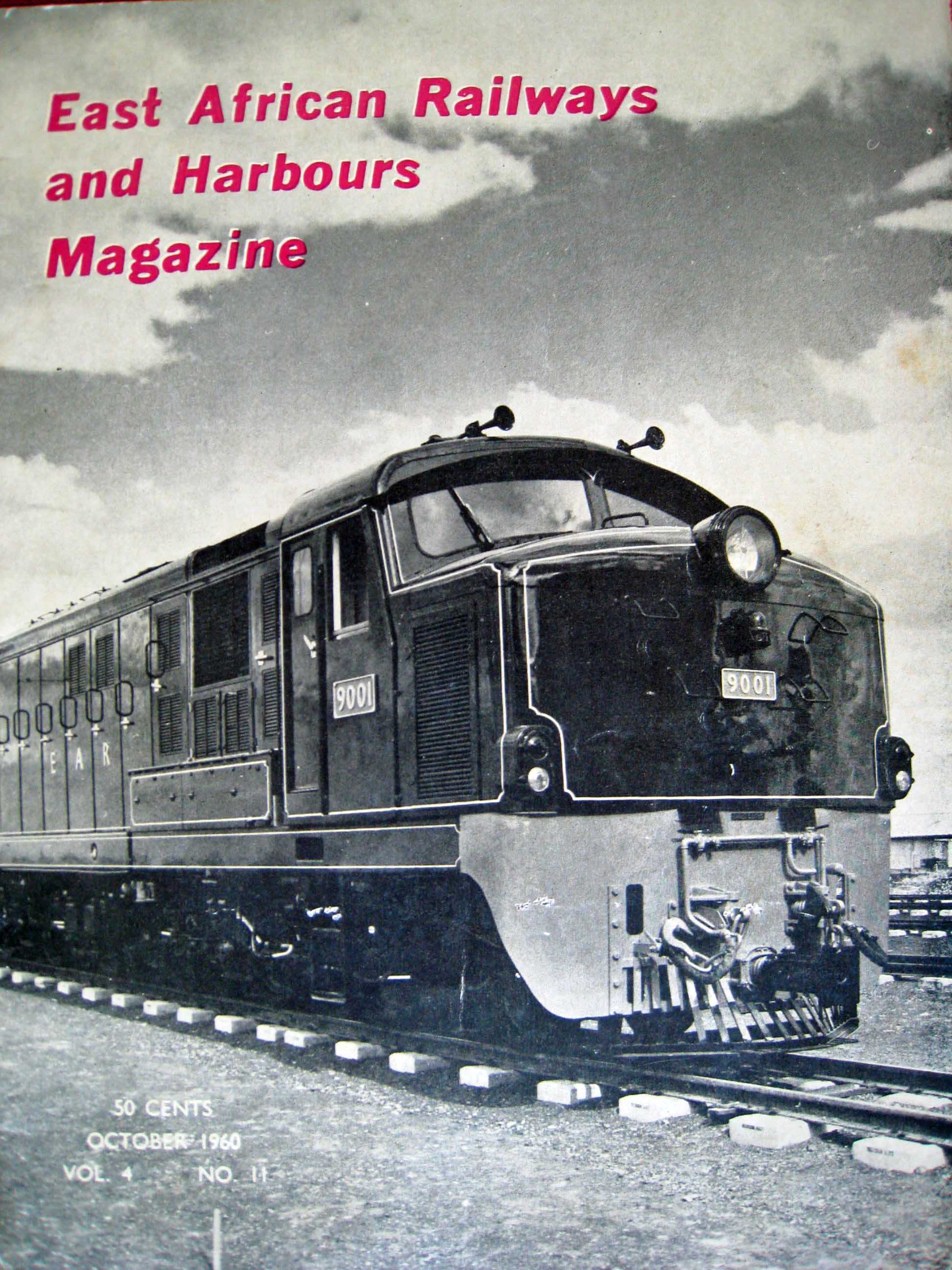

Roger Whittaker & “The Good Old EAR&H”

Roger Whittaker was at the PoW from 1950 to 1954. His alumnus entry says that he is arguably the most famous and well

known Old Cambrian. I would argue with “arguably”!! With worldwide record sales of around 55 million, can any other

OC be more famous? However, the vast majority of his fans would not connect him with the PoW. Trains clearly made a

big impression on Roger the schoolboy, for in later years when he visited Kenya in 1982, Roger the famous singer would

recall those train memories in a song he wrote. Thus the East African Railways and Harbours, and their trains, have

been immortalized in his song “The Good Old E A R & H”. The song was not one of his hits, and to the author’s knowledge

did not make it onto any of his CDs*. It can only be heard on a hard to find video cassette of the BBC TV special that

he made of that Kenya visit. Attempts to reach Roger for an input to this train article were unsuccessful, but we did

get word from him that it would be ok to reproduce the lyrics to the song. The lyrics could not be found on the

internet, so your editor had to listen to the song many times over to get the words.

Roger Whittaker was at the PoW from 1950 to 1954. His alumnus entry says that he is arguably the most famous and well

known Old Cambrian. I would argue with “arguably”!! With worldwide record sales of around 55 million, can any other

OC be more famous? However, the vast majority of his fans would not connect him with the PoW. Trains clearly made a

big impression on Roger the schoolboy, for in later years when he visited Kenya in 1982, Roger the famous singer would

recall those train memories in a song he wrote. Thus the East African Railways and Harbours, and their trains, have

been immortalized in his song “The Good Old E A R & H”. The song was not one of his hits, and to the author’s knowledge

did not make it onto any of his CDs*. It can only be heard on a hard to find video cassette of the BBC TV special that

he made of that Kenya visit. Attempts to reach Roger for an input to this train article were unsuccessful, but we did

get word from him that it would be ok to reproduce the lyrics to the song. The lyrics could not be found on the

internet, so your editor had to listen to the song many times over to get the words.

Roger introduces the song with a monologue. “When I was a boy, the railway meant so much more to me than the

abolition of the slave trade 2 or the opening up of the country, because it was the train that took us up the hills

to school and brought us home again or down the hills to the coast and then brought us home again. They were the

East African Railways and Harbours or for short the good old E A R & H. No boy ever had a railway quite as fine as

mine.”

The song has an up tempo country and western sound with banjo and steel guitar.

1st Verse/Chorus

Oh, the good old E A R & H would get me there on time

Those mighty engines rolling down the line

And no boy ever had a railway quite as fine as mine

Oh the good old E A R & H, (oh) the good old E A R & H

Now when I was a kid I used to play

While the train would rock and roll and swing and sway

And as she pulled us up the grade slowing all the way

Oh, this is what the wheels would have to sing

We would sing along with what they had to sing

And they’d sing, no I can’t, no I can’t, (repeated)

Again they’d sing, no I can’t, no I can’t, (repeated)

That train, oh that train.

Chorus

Now when I was a kid I’d ride a train

That took me up to school and home again

At the end of school aboard that train, our only joy would reign

As down the grades the wheels would keep on saying

They’d say yes I can, yes I can, (repeated)

And they’d say yes I can, yes I can, (repeated)

Chorus

Now somehow it just don’t seem the same

They’re using diesel fuel to pull that train

The old wood burners sitting down in a museum

You don’t ride on ‘em, just go down and see ‘em

Oh it’s sad to see them standing in a museum

Chorus

The final verse mourns the demise of the steam engine, a sentiment that those of us who used the trains completely

empathise with. Such is progress. Perhaps the current generation of schoolboys will harbor similar nostalgia for

diesels when they are in turn replaced by maglev (magnetic levitation) trains or whatever the prevailing technology is.

* In addition to the video cassette, the music was released on an audio cassette entitled 'Roger Whittaker in

Kenya - A Musical Safari' issued by Tembo Music Ltd 1982. Reference 8124 494. Info courtesy of Brod Purdy.

There was also an LP issued called "Roger Whittaker in Kenya: A Musical Safari - Stereo 812.949-1. Released 1-1-1984.

(Info courtesy of Malcolm McCrow)

Soundclip (35 secs) of the chorus of

“The Good Old E A R & H”.

Press the Play button. It should play on your installed media player

EAR 58 Class Garratt.

Photo courtesy of Kevin Patience

b

d

Memories of the School Train from Kampala to Nairobi, 1956-1961

Martin Langley relates his own account of the journey between home and

school

The train journey between Kampala and Nairobi took around 24 hours. There was a lot of emotion in those train trips between

home and school, from the euphoric highs of homeward bound out of Nairobi to the depressing despondency of the

schoolward journey from Kampala. It was a very testing time for the still raw emotions of an adolescent, from

constraining the urge to burst into tears on the one hand to curbing excesses of jubilation on the other. Departing

from Kampala in the rabble years was an early exercise in cultivating a good old British “stiff upper lip”, for one

did not “blub” in public!!

A few days before the impending departure for school, the old tin trunk was reluctantly dragged out and slowly filled

with the coming term’s clothing, spare shoes, the ubiquitous “tackies” and other footware depending on the sport to be

played. Mother would fuss around with her pen and bottle of black marking ink to make sure each item of clothing was

labeled according to school regulations. Later the pen and ink gave way to a ball point pen device making things much

easier, technology thus reaching the most mundane of chores. Then, like a condemned man’s final meal, there was the

de rigeur visit to the local grocery store, affording us the bitter-sweet opportunity to select goodies for the tuck box.

Sweetened condensed milk was probably the most prized and sought after delicacy (if one could call it such) at school.

Baker’s brand custard creams were high on the list. Other favourites were jelly crystals, Marie and ginger biscuits,

Smarties and other forms of chocolate and licquorice. Many were the ways to eat a custard cream, including separating

the two halves and eating the bottom half (with filling) last to heighten the enjoyment of the sweet sensation.

In Kampala when we lived on Kololo Hill we used Kololo Grocers, the local Asian owned duka, for tuck box requirements.

Later we moved to Kyadondo Road near town and shopped at Souza Figureido’s in downtown Kampala, a relatively upmarket

grocery, sort of a tropical mini version of Harrods food store. Mr. Figureido, a portly and jolly fellow of Goan

descent ran an orderly and efficient emporium, which was popular with the colonials. Kampala boys will remember

these and other well known stores such as Draper’s, Men’s Wear and D.L.Patel Press. My Dad used to joke “men swear

at Men’s Wear” where he had his uniforms made.

The train typically departed Kampala station around 3 or 4pm and the morning was spent getting everything together so

that by noon when Dad came home from the office for his lunch, we were usually ready. Lunch on departure day was

eaten in relative silence, then it was a real lump-in-the-throat “kwaheri” to the cheerful domestic help who were

such a big part of our young lives and it was into the Ford Zephyr for the ride to the station. Kampala was such a

pretty town in the late fifties, very tidy and well maintained by the PWD (Public Works Dept). Traffic roundabouts,

parks and median strips typically had well manicured grass and masses of flowering shrubs and other plants.

Bougainvillea, frangipani, hydrangea and hibiscus were ubiquitous and everything was always green in keeping with

the tropical climate. It was no wonder that Winston Churchill referred to Uganda as the Pearl of Africa; it was

beautiful. As the commercial capital of Uganda, it was quite a bustling town, small compared to Nairobi or Dar es

Salaam but full of life. Busy road junctions in Kampala typically had a dais in the middle of the intersection upon

which a traffic policeman stood to direct traffic with his white cuffed arms and his referees whistle blowing

energetically. The native Uganda policeman with his tall navy blue tassled fez adding to his height, was quite

statuesque and always very well turned out, with navy blue cummerbund, shiny black boots and smart starched uniform –

us kids were very impressed by them. Some of the policemen on traffic duty put on quite a show with dramatic arm

movements and gestures, like a marionette, but they were very effective. Around 1957 the first automatic traffic

lights were installed in Kampala, and that caused quite a stir, with the local populace gathering around to watch

them change colour. However, everyone adjusted to them very quickly and they soon became passé.

At the station, the train would usually be there waiting and then came a process of anxious scurrying up and down

carriage corridors looking for an empty “comparty” or seeking compatible friends with whom to share. In the late

50s, Kampala boys included the Palin brothers, Mike Pickett, John Quinnell, the Stanley twins, Harry Brice, the

Dokelmans, Tim Saben (whose mother was a one time mayor of Kampala), Keith McAdam, Colin Townsend and many others.

Already on the train would be one or two boys from the Kilembe copper mines in the foothills of the Ruwenzoris 12

hours west; Winston Shaer was one such boy.

The Railway Station in Kampala around 1960

Courtesy Malcolm McCrow,

http://www.mccrow.org.uk/EastAfrica/Uganda/Kampala.htm

The Kampala Railway Station was a typically solid colonial structure of brown sandstone. While not particularly inspiring from an architectural standpoint it was very functional and for those of us who used it, it had (and still has) a special place in our hearts.

Soon we’d all be on board, hanging out of the windows and waiting for the conductor’s whistle and the shout of “stand

clear of the train” signaling the train’s imminent departure. Finally the conductor would give a final blow on his

whistle and wave the green flag. The Garratt loco would give a toot and slowly with much chuffing and clanking, as the

slack between carriages was taken up, the train would pull out of the station. I’d gaze back at the diminishing sight

of my mother, younger brother and sister thinking (of my siblings) “you lucky so and so’s, you’re staying home while

I’m off to bloody boarding school”!! Eventually of course bro and sis would also have to endure the misery of the

school train to Kenya. As the train trundled through Kampala and suburbs, one would gaze longingly at familiar

landmarks as they slowly passed by. One such was the level crossing on the Port Bell road, down which was the Silver

Springs Hotel, the location of one of the few swimming pools in town where it was a real treat to be taken for a

“goof” (swim) on a hot day. The hotel, not far from Port Bell on Lake Victoria was built to house over-night

passengers on the flying boat service from S. Africa to the UK in the 1930s.

In just over an hour, the train would cross the Nile over the Ripon Falls, just before Uganda’s second biggest town, Jinja, home to the Owen Falls dam and the Madhvani sugar works.

A School Train approaching Jinja Bridge in 1960 - hauled by a 60 Class

Courtesy of Malcolm McCrow,

http://www.mccrow.org.uk/EastAfrica/Uganda/Kampala.htm

After Jinja, as night fell, the dulcet tones of the xylophone would echo down the corridors of the train summoning all to dinner in the dining car. The food was served on those solid EAR&H plates that looked like they would survive a tank going over them. Typical menu items included soup of one kind or another, roast beef with gravy and potatos and finished off with a sponge cake and custard for desert. After dinner the train would hit Tororo on the Uganda border, home of the Tororo cement works, in the shadow of the Gibraltar rock lookalike, the Tororo rock. The last of the Uganda boys would get on at Tororo.

That night on the train away from home was a weird state of limbo where you were neither at home nor at school. It was a time for reflection, as in the quiet darkness, the train trundled onward, swaying to the almost metronomic clickety-clack of the wheels over the rails. From time to time it would stop to take on water or fuel at small sidings or stations in the middle of the night, miles from anywhere. Though the hard green bunks were barely comfortable enough for sleep if you wanted to, invariably the jolting of the train as it came to a stop would awaken one. The silence and the stillness of the African night, as anyone who has lived in Africa knows, is in itself an experience. Apart from the occasional sound associated with the running of a railway, such as hissing steam or the tapping of carriage wheels, the African bush was deadly silent, with only the chirping of insects and the odd animal noise emanating therefrom. On sticking your head out of the window you would be greeted with that clean, fresh bush smell that was even more pervasive after a rain shower.

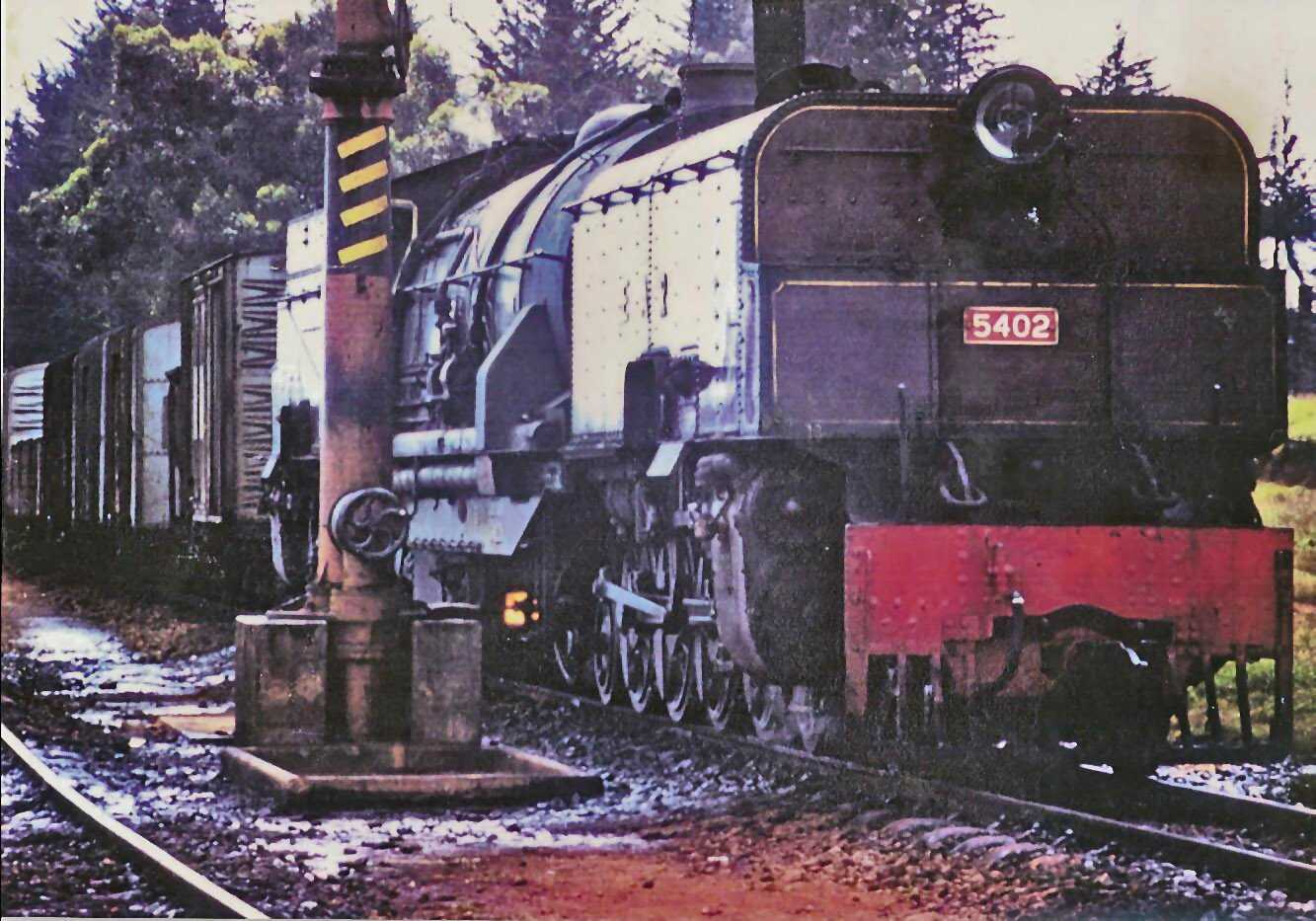

A 57 class Garratt, typical of the loco that would have hauled school trains from Kampala. The 58 & 60 classes

were also used. The 59 class was too heavy for the Uganda line.

Photo

courtesy of Kevin Patience

EAR 1961 route map - Kasese – Kampala - Nairobi.

Courtesy of Malcolm McCrow

And who can forget the smell inside the train! A wine buff might describe it thus: a preponderance of burnt hydrocarbon and heavy machinery with overtones of old tobacco, dark green leather, human essence and freshly turned earth. Hints of culinary concoctions occasionally assail the senses and all combine to leave a lingering, distinctive and slightly acridic aftertaste.

One hated the night to be over because when it was, you knew you were over the border into Kenya and drawing ever closer to school and all the uncertainties of the coming term. In the early days, as a rabble you tended to stay put in your compartment. To venture out was to risk crossing the path of a senior who could summarily “invite” you to a compartment full of leering peers for initiation ceremonies. On passing, you averted your gaze and tried not to look him in the eye, for to do so might be construed as insolence and merit unwelcome attention. I once witnessed a scared and pale rabble being made to eat a cigarette (yes, eat, not smoke). His pallor went from white to green as he chewed on the tobacco, his mouth opening between chews to reveal a revolting khaki slime. Fortunately, I would say that most seniors were above tormenting junior boys, but there was always the sadistic or immature minority, perhaps newly ascended to the rank of senior, who reveled in their new found power. One respected those senior boys that did not indulge in that sort of thing.

A feature of the Kampala-Nairobi train trip was the huge altitude changes encountered en route: from the approximate 4,000 ft elevation of Kampala to a little over 9,100 ft at Summit down to the floor of the Rift Valley at about 6,200 ft then up the Eastern Escarpment to 7,800 ft then down to Nairobi at about 5,400 ft. Those changes in elevation resulted in some spectacular vistas from the train window along the way!

Graph (modified) courtesy of Kevin Patience from his book “Steam Twilight”

With Tororo and Uganda now behind us, the train begins the hard slog up the Kenya highlands and you can hear the Garratt

labouring as it hauls its heavy load up the steep inclines. Familiar names drift slowly by, Broderick Falls, Turbo are a

couple that come to mind, as the train chugs up the grade. The air becomes ever more crisp and clean as altitude is

gained. In the dark early hours of the morning the train reaches Eldoret, also known as “64”. The origin of 64 is

explained in “Pioneers' Scrapbook. Reminiscences of Kenya 1890 to 1968”. “When Government surveyors pegged out blocks

of land for which settlers could apply, each future farm received a number. Number 64, on the Sosiani River, was leased

to Willie van Aardt. He found it unsuitable for farming, so it was selected as the site of a Post Office, opened in 1910.

Telegrams went by heliograph to Kapsabet, the nearest point where there was a telegraph line. This township in embryo

was known as '64' until officially named Eldoret in 1912 by the Governor. By then the European population of the

Plateau had grown to 153 males, 96 females and 236 children, half of these under ten.” Another version says it was so

called because it was 64 miles from the newly built Uganda Railway railhead at Kibigori. Either way, there would be many

sleepy mutterings of “yurra yong” by those awake, in recognition of the town’s “kaburu” (South African) settlers.

Many of the descendants of those settlers attended school in Nairobi and boarded the train at Eldoret.

'Eldoret was also the junction for the short Kitale branch line, from the north, which joined the main line one station

west of Eldoret at Leseru; kids for the Hill School were woken at Leseru to get dressed prior to arrival at Eldoret.

There would be a number of

boys from the Kitale region joining the train at this stop such as Brod Purdy (whose story appeared earlier) and others,

who would bang loudly on compartment doors seeking a berth.

Because of the noise generated by activity at Eldoret station,

most passengers would be half awake as the train left the station and passed the Highlands girls school just outside

the town. Some of the girls would break bounds to see the train swing by in the hopes of glimpsing a sweetheart or

brother waving from the windows. In the early morning light you could see the girls, evident by their squeals and

shrieks, waving frantically. Typically there would be maybe half a dozen brave (or foolhardy!) girls just below the

embankment that the train was passing over. Breaking bounds to greet the train was strictly forbidden and penalty if

caught was gating for the term and in the case of one girl, demotion from prefect. In the same situation at the POW,

the penalty would doubtless have been six of the best from Flakey!

After Eldoret the train would continue on its upward trek, and soon that evocative bong bong of the xylophone would

announce breakfast in the dining car. Next stop of significance would be Timboroa, at 9,001ft, the then highest railway station in the British commonwealth. While the Garratt watered up, a stroll along the platform in the bracing clean air was efficacious and refreshing after the long night. Usually sunny but often misty and chilly, Timboroa seemed an almost deserted little outpost with few people around except railway personnel, passengers and the ubiquitous young hawkers from nearby villages peddling their wares. “Plerms, ahplez, biskwits” (plums, apples, biscuits) they would sing out in their quaintly accented English. Ron Bullock relates an incident with a hawker. “We were at Timboroa I believe - wherever the station with the dining room was anyway. It was dark, I suppose 9-ish. The engine was making those whooshing sounds as resting engines will. The platform was quite lively and the local hawkers were particularly prominent. One fellow passed by our carriage with his mahindi and ndizi and cookies or whatever laid out on a tray held above his shoulder for clients to see in the gloaming that was all that passed for light. Someone - I used to know who it was but that memory is fortunately long lost - someone put a lighted squib on the tray, and of course the bearer had travelled some feet before it exploded. I will not try to relate the ensuing mixture of consternation among the occupants of the platform and mirth on the part of we few dastardly schoolboys. In more recent and calmer moments, I have sometimes wondered what this little prank cost of the vendor's meagre resources.”

Photos courtesy of Malcolm McCrow

Not long after Timboroa, a signpost would announce Summit, the highest point on the Kenya-Uganda line at 9,136ft.

The photo shows a pair of 50 class Garratts double heading a freight train passing Summit, heading for Nakuru.

Having passed Summit, after crossing the Equator, the train would pick up speed as it headed down the escarpment towards

Nakuru on the floor of the Rift Valley. The beat of the locomotive would change and the chimney note would go from

laboured individual choof-choofs to a muffled but exhilarating staccato as it sped down the inclines. At this stage,

it was an easy canter for the powerful Garratt. When lightly loaded, a passenger train headed by a Garratt would get

up to speed pretty quickly, as evidenced by this sound clip of a South African Railways GMA Garratt 3 pulling out of a

station. Note the typical Garratt double beat of the stack, clanking and chuffing as she gathers speed, reminiscent of

an EAR Garratt descending from Summit, so crank up the volume and have a listen.

Soundclip (53 secs) of a Garratt pulling out of a station.

Press the Play button. It should play on your installed media player

Poking one’s head out of the carriage window into the 25-40* mph slipstream was an invitation to get pinged by a speck

of soot. At times, a smut would find its way into one’s eye, a very uncomfortable even painful experience. We all

have our favourite memories of the school train, little incidents that stick in the mind. Mine was cruising down from

Summit toward Rongai the last big station before the important junction of Nakuru, where the Kisumu line joined the

mainline. The sky was blue the sun was shining and the train was loping along at an easy canter. Someone in the

compartment had brought in a wind-up gramophone and a Doris Day record was on the turntable. “Take me back to the

black hills, the black hills of Dakota” she was crooning in that mellifluous voice of hers. And I remember sitting

there thinking gloomily “bugger the black hills of Dakota, take me back to the green hills, the green hills of Kampala!”

To this day, hearing Doris Day, reminds me of the school train.

* Author's note- From memory, I estimated that the train cruised at 45-50mph (downhill) but Malcolm McCrow has advised

that to his knowledge, the maximum speed permitted between Kampala and Nairobi was 40 mph at Naivasha and that the

train normally travelled at between 25 and 30 mph. This is borne out by the 1962 EAR&H timetable where the scheduled

total travel time for KLA-NBI was 23hr50min. After allowing for approximately 13 stops @ say 15min each, net travel

time was 20hr35min resulting in an average speed of 28mph over the total distance of around 580 miles.

And so before you knew it the train would be pulling into Nakuru station, where a multitude of bronzed farmers and their

schoolboy offspring would be thronging the platform. To this Uganda boy the Kenya farming types always seemed to be of

sturdier stock than us city boys. While they were out there trying to eke out a living from the sometimes unyielding

soil and having to deal with pest and pestilence, wild animals, sick animals, the weather and the vagaries of farm life

in general, we were having to make life altering decisions such as “do I ride to town on the pushi or on the piki-pik?”

The boys that got on in Nakuru were from the Nakuru area itself and from the Kisumu line that included the farmlands

surrounding Lumbwa, Londiani, Kericho, Molo etc. The photo shows the new Nakuru station that was opened in 1957.

And so before you knew it the train would be pulling into Nakuru station, where a multitude of bronzed farmers and their

schoolboy offspring would be thronging the platform. To this Uganda boy the Kenya farming types always seemed to be of

sturdier stock than us city boys. While they were out there trying to eke out a living from the sometimes unyielding

soil and having to deal with pest and pestilence, wild animals, sick animals, the weather and the vagaries of farm life

in general, we were having to make life altering decisions such as “do I ride to town on the pushi or on the piki-pik?”

The boys that got on in Nakuru were from the Nakuru area itself and from the Kisumu line that included the farmlands

surrounding Lumbwa, Londiani, Kericho, Molo etc. The photo shows the new Nakuru station that was opened in 1957.

After Nakuru, there was Gilgil and Naivasha where a few more got on, then on we chugged across the floor of the Rift

Valley and up the Eastern escarpment. Now we were really getting close to Nairobi and as the suburbs merged into the

city, most boys were a picture of silent brooding, dreading the moment when the train would come to a shuddering halt.

Typically there was a master there to meet us, like Johnny Riddell the PT master, trying hard to be jovial amid the

gloomy faces. And so, into the bus or green school lorry we would pile, dragging our tin trunk, for the final silent

ride to what seemed like jail and a long way from home.

A 60 class heading a passenger train rounds a bend, probably in the early or mid 1960s. Note the chimney shape, indicating

a Giesl ejector has been fitted – see Appendix 4 for an explanation of this modification.

Photo courtesy of Kevin Patience

b

d

The narrative so far has been from a passenger’s perspective, from behind the engine. But how do things look from the

engine driver’s cab? An EAR engine driver’s story follows.

b

d

Reminiscences of an EAR Garratt Engine Driver

FIVE FOOT THREE to THREE FOOT THREE by Archie Morrow

Archie Morrow was an Irish railwayman who joined EAR in 1954. He ended up driving Garratts and posted his memoirs of

those times on the website of the Railway Preservation Society of Ireland (RPSI) in the Winter 1998/99 issue of their

journal “Five Foot Three”. The title of his memoir, ‘Five Foot Three to Three Foot Three’ reflects the gauge of

Ireland’s railways and that of East Africa. Sadly Archie Morrow passed away in 2004 and the following is reproduced

with the kind permission of the Secretary of the RPSI

[Around 1951] I applied to the Crown Agents in London for a job as locomotive driver anywhere in the world. I received an

application form from the East African Railways and Harbours in March 1954 and I was in Nairobi on my birthday,

24 July 1954.

Archie Morrow in 1954 shortly after arriving in Nairobi.

The picture was taken in front of pre-fab tin quarters that housed railway personnel.

His son Lawrence says the pre-fabs were extremely hot and that later the family moved

to flats beside the local sports ground. Ironically, had the Morrow family remained in Kenya

after independence, Lawrence was destined to attend the Prince of Wales School.

Photo courtesy of Lawrence Morrow

This was a Sunday and none of the railway offices were open and I was taken to be signed into the Railway Bachelors’

Quarters but we never got past the Railway Club. As a new Irish recruit, I was made very welcome and ended up the

worse for drink and without lunch. I was told later that I had sung “When Irish Eyes are Smiling” - badly. At

dinner that evening I think I was set up and given a very very hot curry but with the drink in me I didn’t turn a hair.

Later that evening I went to bed and remember nothing until the next morning when I awoke to the words, “Chai B’wana”,

and an African face looking through the mosquito net. For a few minutes I thought I was Sanders of the River!

I attended Nairobi Locomotive Training School to learn about the Westinghouse brake which was used in Kenya because

vacuum is difficult to create at high altitudes. After passing the Westinghouse brake test I was transferred to Nakuru

which is the capital of the Rift Valley province of Kenya. The Great Rift Valley is an earth fault that runs throughout

East Africa from the Red Sea to Malawi and is believed to be the place where man began to walk upright. [In Archie’s

case this probably took place some time on the Monday. – RPSI Ed] Nakuru is just south of the Equator and in the Rift

Valley but, at an altitude of just over 6000 feet, has a wonderful climate.

Nakuru shed was quite modern steam-wise, servicing a large fleet of rigid and articulated oil-burning locomotives and

having a drop pit, wheel lathe and machine shop. It supplied motive power to work Nakuru - Nairobi - Mombasa,

ruling grade 1.5%; Nakuru to Kisumu, ruling grade 2%; Nakuru to Eldoret, ruling grade 1.5% plus the Gilgil to

Thompson Falls and Rongai to Lake Solai branch lines. (2% = 1 in 50 in old money). After learning routes and being

passed by the Locomotive Inspecting Officer (LIO), I worked pick-ups for about three months. The shedmaster, Don Owens,

called me to his office and gave me my first Garratt, No.5302, just out of Nairobi workshops after a heavy overhaul.

Did I feel some kid?!

Nakuru shed in Archie Morrow's time.

Photo courtesy of Lawrence Morrow

A picture of Archie Morrow’s Garratt, No.5302 was found on the web -

Archie Morrow’s first Garratt, East African Railways #5302.

(Chris Greville collection).

This engine was a GA (later 53) Class Garratt delivered to Tanganyika Railways in 1939.

My first trip on 5302 was a night freight to Eldoret, returning to Nakuru after rest the following night with another

freight. As we were about to leave, three LIOs (Locomotive Inspecting Officer) appeared out of the gloom and asked me

not to rock the boat as they would be sleeping in two coaches at the rear of the train. One of them, as an afterthought,

said, “Driver, if you have any problems do not hesitate to wake us”. The trip was uneventful until we were approaching

Visoi where the signal was at danger. The signal dropped and I released the brake and proceeded to enter the station.

As we passed over the points, to my horror, I could see the pointsman turning points under the boiler unit of the

Garratt. I slammed on the emergency brake, thinking that the LIOs would now be tossed out of bed and far from pleased.

The train stopped with the front unit of the engine on the main line and the rear one entering the crossing loop.

That was my introduction to Garratt working! Fortunately, the incident was held to be not my fault and I received a

commendation for stopping quickly.

I had 5302 for about nine months without any more problems. In late 1955 Nakuru shed received an allocation of new 60

class Garratts. They ran like sewing machines. Some wag of a driver said,” The working class can kiss my ***

I’ve got a 60 class at last!” I received No.6018 “Sir Charles Dundas”, all this class being named after colonial

governors.

One trip I will always remember was when coming back from Kisumu with a mixed train. On a 2% upgrade between Fort

Ternan and Lumbwa we ran into a swarm of locusts and slipped to a standstill. The cab was swarming with them and they

were frying on the smokebox and hot pipes. Luckily some shrubbery was growing close to the line and we had a panga

(African knife) on board. The fireman and I cut some heavy branches with plenty of leaves and pleated them into the

cowcatcher so that they brushed the rails. Still slipping, we got away and arrived in Lumbwa one hour down. My fireman

was very partial to fried locust and had an excellent lunch, indeed I had trouble keeping him in the cab as he kept

making trips to the smokebox to harvest the best cooked specimens. I tried a few but my palate would not accept them.

In 1956 there was a very bad runaway between Lumbwa and Fort Ternan. A double-headed heavy freight with a 57 class

Garratt and a 29 class 2-8-2 locomotive left Lumbwa and gained speed very rapidly on the 2% downgrade. In the brake van

at the rear the guard panicked and applied the emergency brake which jammed. The driver then had no way of building up

air pressure in the train pipe and the train, by then out of control, derailed between Fort Ternan and Koru, killing

one Sikh driver, two African firemen and one African guard. Bill Ewart, the driver of 5702, lost a leg and was eventually

sent home. I had home leave in 1957 and visited him in Glasgow. He died a few years later.

I worked the breakdown train with a 75-ton crane on this accident with very little rest for over two weeks, although my

overtime was substantial. After this accident no driver was allowed to take charge of a train on a 2% grade without at

least two years experience on the Westinghouse brake. Fortunately, by this time I had qualified.

At this point, a few words on the Westinghouse Automatic brake might be appropriate. It is operated by compressed air

which on the EAR&H was furnished by two Westinghouse compressors controlled by a steam governor to 100 psi. and stored

in the locomotive’s main reservoirs. This air is then fed to the train pipe and auxiliary reservoirs on each vehicle in

the train through the driver’s brake valve at 80 psi. The air to each vehicle is controlled by a quick acting triple

valve and the brakes remain off as long as train pipe pressure is held at 80 psi. Any reduction of train pipe pressure

from whatever source e.g. driver’s brake valve, guard’s emergency valve, burst flexible hose or passenger communication

cord being pulled activates the triple valves and allows compressed air from the auxiliary reservoirs into the brake

cylinders at a rate proportional to the severity of reduction of the train pipe pressure - hence the term “Automatic”.

On the long severe continuous down grades on the EAR&H e.g. Timboroa to Rongai (around 60 miles of 1.5% down grade)

it was imperative that the train pipe and auxiliary reservoirs were recharged at regular intervals and this could only

be done when the driver’s brake valve was in the full release position. During this vulnerable period speed would have

increased rapidly and the driver had to use Retainers to maintain control.

On every vehicle on the Kenyan section of the EAR&H the brakes were released through a valve at waist height. When

closed, this retainer valve held compressed air in the brake cylinders at 15 psi and exerted a continuous braking

effect. This was a more modern version of the procedure of pinning down wagon brakes which used to be practised in

the British Isles. Sections of track where retainers were required were indicated by a “R” board at which it was

compulsory to stop. The driver then had to decide, after taking into consideration the weight of the train and how

effective the brakes had been so far, how many retainer valves he should instruct the fireman to close.

The building of the Kenya Uganda Railway from Mombasa to Kisumu must rank high in the top ten great railway building

engineering achievements of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the Nakuru to Kisumu section being the

most difficult with its innumerable steel viaducts over deep chasms and valleys and still keeping to a 2% ruling grade.

A great friend of Jane and I in Nakuru was Florence Preston, widow of R.0. Preston, the working engineer who was in

charge all the way from Mombasa. Florence had the privilege of driving the mythical Golden Spike when the railway

reached Kisumu on 20 December 1901. [Editor’s note: The terminal of the Uganda railway was originally named for

Florence Preston viz Port Florence. At the time the Uganda border followed the Rift Valley.]

The Kisumu line started off from Nakuru at an altitude of just over 6000 feet and climbed to Mau Summit at 8700 feet,

all 2% upgrade for about 45 miles. Then it was 2% downgrade all the way for about 60 miles to Koru, at an altitude of

4000 feet. After that it was more or less level through the Nyanza sugar fields to Kisumu on the shores of Lake

Victoria at an altitude of 3700 feet. Kisumu is the capital of the Nyanza province of Kenya and has the highest

dockyard in the world.

In the early part of the century this area was classed as a white man’s grave. Fortunately, when I started to work to

Kisumu health conditions had improved immensely. After the rains - and Kisumu got a lot - the grass grew fast and lush.

This encouraged the hippopotami of Lake Victoria to come out at night and graze on the grass that grew between the

engine shed and Hippo Point. Sometimes I thought that all the cars in Kisumu were there to shine their headlights

across this grassy meadow. We drivers and firemen had the problem of getting from the engine shed to the running

room without getting between a hippo and the water. Statistically, there are more humans killed by hippos than by

any other wild animal in Africa, just because they got between the hippos and the water.

I have lots of fond memories of driving on the Kisumu line but two stand out and are worth recording. One was descending

from Mau Summit at night and from a distance seeing an electrical storm over Lake Victoria, a sight I am sure only

railwaymen or insomniacs enjoyed. Another one was coming back from Kisumu on the long 2% climb from Koru to Mau Summit

when African children of all ages would run out of their huts and do a tribal dance to the rhythm and song of a

Beyer-Garratt locomotive with a full load.

In 1957, after coming back from home leave, I was transferred to Eldoret due to a housing shortage in Nakuru. I was

there for nine months, learning the road and on caboose workings to Kampala in Uganda. The line between Tororo and

Kampala had been built in the 1930s when money was scarce and was momentum graded. This meant that trains were loaded

for a 1.5% grade but had to negotiate dips in the line which were graded at 2%. How this was managed was by running

fast enough into the dip to gain sufficient momentum to get out of it again. This was not a job for the faint-hearted

and one Eldoret driver had such problems as to clock up a record 28 days pay fines in one month. The Chief Mechanical

Engineer was in a quandary as if he sacked him he would have to pay his fare back to the UK. The problem was solved by

promoting him to Locomotive Inspecting Officer where he could do no more harm. I believe he was the one who told me to

wake him if I had any problems on my 5302 incident.

In the late fifties and early sixties some 59 class Garratts were allocated to Nakuru shed. There were thirty-four in

the class, the last and largest Garratts ever built, with a tractive effort of 83,350 lbs., an overall length of almost

105 feet and a weight in working order of 252 tons. They were named after the mountains of East Africa.

The Nakuru allocation was to work a daily heavy freight to Mombasa, a four day round trip which meant caboose working

with two crews for each locomotive, one working and one sleeping, changing over at eight-hour intervals.

Three incidents worthy of note happened to me when on this run. One morning after leaving Voi at first light my

fireman drew my attention to a herd of elephants running along his side of the train and they appeared to be gaining

on us. By regulating my speed I was able to keep them alongside for about a mile, a sight I will never forget. Voi is

in the Tsavo Game Park and is the junction for Moshi and Arusha in the foothills of Mount Kilimanjaro which, at 19,340

feet, is the highest mountain in Africa. Despite this, the first of the 59 class was not named after it as one might

have expected, that honour going to Mount Kenya, appropriately enough I suppose. The class as a whole seemed to be

named in a random manner.

On another trip coming back from Mombasa with Garratt No.5923 “Mount Longonot” we hit and killed a giraffe. There was

an African village nearby and the kill had been seen so I knew the giraffe would soon disappear. At the next crossing

point I had a clear line and decided not to report it as I did not want to be delayed there after four days away from

home. On examination of the locomotive at Nakuru I found a dent high up on the streamlining of the front tank where the

giraffe’s head had whiplashed. I still said nothing about it and several months later I heard someone wonder how a dent

could get up there!

One Up and Two Down were the upper class express passenger trains that ran daily between Mombasa and Nairobi, both