(Best viewed with screen resolution set at 1024 x 768 pixels)

Philip Fletcher, OBE

Headmaster of the Prince of Wales School

1945-1959

(Freddy Yowell Studio, Nairobi)

Foreword

Having renewed their contact through the Old Cambrian Society website after a gap of forty-five years, Brian

McIntosh and Christopher Collier-Wright (class of 1959) decided it was time for an old boys’ appreciation of Philip

Fletcher. Working from their respective homes in Pennsylvania and Bahrain, they began by combing the 1959 Impala magazine

for articles about Mr. Fletcher’s retirement. Then, thanks to the wonders of email, it was possible to pursue several

leads and gather fascinating details about the Headmaster’s early life and career from sources as far away as Australia.

Closer at hand, they found memories of the man known as PF, Pink Percy, Vluitjie, Flakey or Jake in the Alumni section of

the school website, and they received other contributions through correspondence with a number of Old Cambrians. It was,

so to speak, a ‘harambee’ effort with many hands pulling together.

Philip Fletcher, or PF as the staff knew him, was a decent, caring, and dedicated man whose fourteen

years of service as Headmaster epitomized the school’s motto, “To the Uttermost”. He set a lofty tone, and he led by

example. The public PF was decisive, driven, and intensely loyal to his boys; the private PF (to borrow a Churchillian

quip) was something of a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma. One thing about PF was always clear, however, and

that was his vision: “I should think something was wrong,” he said in his 1959 Queen’s Day speech, “if all boys were

always happy; for school is a training for life, and life is full of rough patches through which one must live and help

others to live. But I do think it tremendously important that there should be an atmosphere of happiness, confidence,

trust, mutual liking and respect and that boys should consciously cherish this and do their best to maintain and increase

it. Like all the precious things of life, it can easily be lost.”

On behalf of that majority of Old Cambrians who were happy most of the time at school and who flourished

under PF’s leadership, this appreciation is dedicated with affection and respect to the memory of a great man.

Early Life and Career

Philip Fletcher was born on 3 March, 1903 in Hoylake-cum-West Kirby, Cheshire. His parents were William

Charles Fletcher and Kate Edith Penny. He attended Homefield Preparatory School in Sutton from 1913 to 1916, and the

Highgate School in London from 1916 to 1922.

In the 1959 Impala, the Vice-Principal ‘Fritz’ Goldsmith writes, “From his earliest years, ‘P.F.’ had lived

in an atmosphere pervaded by schools. His father, W. C. Fletcher, Second Wrangler at Cambridge in 1886 or thereabouts, was

the Headmaster of the Liverpool Institute from 1896 to 1904, and the first Chief Inspector of Secondary Schools from 1904

to 1926. A Fellow of St. John's College, Cambridge and one-time President of the Mathematical Association, he is still

remembered as a brilliant teacher of Mathematics.

“His son, Philip, born in 1903, was at Highgate School from 1916 to 1922 and became its youngest Head of

House. After spurring a very small House to win most of the Inter-House Competitions, and monopolising the Mathematical

prizes, he finally became Head of the School.”

Responding to our inquiries about PF’s own school days, Theodore Mallinson of the Highgate School Foundation

Office wrote to us that PF “was indeed here from 1916-1922 and you certainly ought to have a special section on him in your

website. He was a great man. I knew him when I was a boy at Marlborough from 1922-1927. Sadly (at Highgate) we do not

have in our records any decent photographs of him; however, all is not lost: there was a whole school photograph in 1919

and he must be in that.”

During a visit to Highgate in the summer of 2005, Christopher Collier-Wright discovered that the

Highgate School photograph taken in 1919 was a yard wide, with five (or so) lines of boys. Seeking out the fifteen year

old Fletcher would have been a daunting task. Fortunately, his name was one of a few included on an accompanying list,

and Gordon Tweedale, Director of Art at Highgate, kindly photographed the image for us.

Philip Fletcher, 15, at Highgate School, London in 1919

Another discovery at Highgate was Philip Fletcher’s entry (below) in the Valete list published in the School journal, The

Cholmeleian, in December 1922 which testifies to his wide interests and abilities:

And finally, on the boards that line the walls of Highgate’s “Big School” hall where honours awarded to old boys are

listed, the following entry appears under University Scholarships: “P. Fletcher 1921 St John’s College Cambridge.”

Moving on to PF’s time at Cambridge, 1922-25, we found that another of our correspondents, Jonathan Harrison of the library of St John’s College, Cambridge was

able to turn up a splendid photograph showing PF as a member of the Eagles Club in 1925, which we copy below.

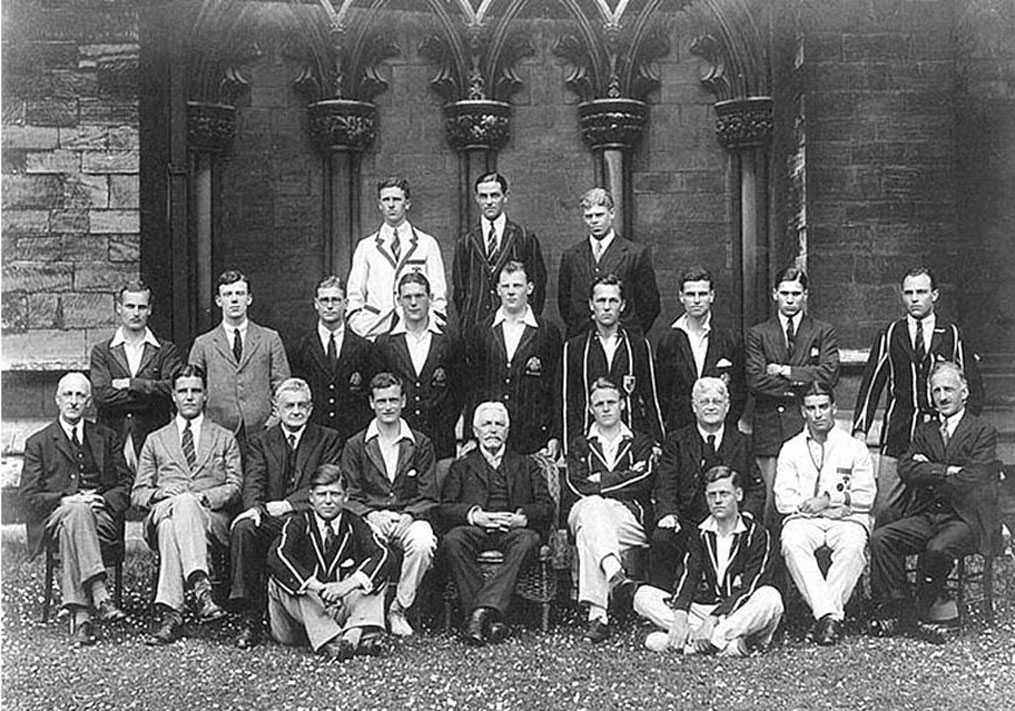

1925 group photo of The Eagles, a social and sporting club at St John’s College, Cambridge.

Philip Fletcher, aged 21, stands in the second row from the back, second from the left.

(Reproduced by kind permission of the Master and Fellows of St John's College, Cambridge.)

A second photo in the Eagles Club album held in the library of St John’s College shows Philip Fletcher and his fellow

members in evening attire. The club emblem seen on the jacket pockets, an eagle, is the symbol of St John the Evangelist.

Membership of the Eagles was (and is) restricted to those who displayed sporting prowess – in the case of Fletcher,

in rowing.

Philip Fletcher, standing second from right at the Eagles Club dinner in Cambridge in May 1925.

(Reproduced by kind permission of the Master and Fellows of St John's College, Cambridge.)

Revisiting for a moment the Fritz Goldsmith article in the 1959 Impala, we read that “In 1922 PF went as Philip Baylis Scholar

to St. John's College, Cambridge, where he rowed in the First May. Boat in the crew that won the Ladies' Plate. He was

placed in the First Class in Part I of the Mathematical Tripos in 1923, and in Part II in 1925. He then spent a year as

Jane Eliza Procter Visiting Fellow at the Graduate College, Princeton, in the U.S.A., during which time he was able to

indulge, in the Rockies, his passion for walking and mountaineering, as he did later in Europe, Australia and Tasmania.”

We contacted Matthew T. Reeder of Princeton University’s Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library with an inquiry

about PF’s year at the Graduate College. He responded by graciously offering a free photocopy of PF’s personal file. In

the file there is a letter from the Vice Chancellor of Cambridge University, A.C. Seward, to President Hibben of Princeton

stating, “I have nominated Mr. Fletcher to hold the 1925 Proctor Fellowship because in my opinion he is not only a keen and

able student, but a man of wide interests; and he is particularly interested in Adult Education.” The letter is dated May

4th 1925.

From other correspondence and documents in the file, we learned that in September 1925 PF left his home at

47 Cromwell Avenue, Highgate, London and sailed for America on the SS Alaunia. At Princeton he was enrolled in a one-year

MA degree program, and he was paid a Fellowship stipend of $2,500 for the year. His courses included Hydrodynamics and

Elasticity, Electron Theory of Matter, Celestial Mechanics, Stellar Astronomy, Statistical Mechanics, Kinetic Theory of

Gases, and Quantum Theory. Not surprisingly, he did well: on February 23rd 1926 the Dean of the Graduate School reports

to Cambridge that “Mr. Fletcher is doing finely. His work is of first-rate character and his personal qualities are very

attractive.”

After graduation, and being anxious to see as much as possible before going home, PF traveled west to

California, north to Vancouver, and eastward across Canada before ending his journey in New York. From on board the SS

Minnedosa, he wrote the following note on August 26th 1926, thanking the Princeton Graduate Office for expediting his dealings with the

Canadian and U.S. Immigration authorities:

“Dear Mrs. Creasy,

I never thanked you for sending me the document certifying that I really had been at Princeton and was not a thug or a

blackmailer; it relieved my mind considerably to have it.

Well, at last I am bound away for home, after having had a glorious and exciting trip around the country;

10,000 miles of it in fact. Everyone I met was nice to me and helped me to see things that the common or garden type of

traveler would not be able to see; so the trip was a fitting finish to the wonderful time that you all gave me at

Princeton; never shall I forget this year. I hope that you will all be equally nice to my successor.

Upon returning from America, PF became an assistant master at Marlborough College. He was there from

1926 to 1934, but from 1931 to 1933 he took a break of seven terms to teach at Geelong Grammar School in

Australia. The Curator at Geelong, Michael Collins Persse, writes of PF that “He is part of a long series of

connections with Marlborough, whose present Master, Nick Sampson, was head here till last June.” (Geelong is an

internationally famous boarding school, the main campus of which is situated near Corio, across Port Philip Bay from

Melbourne. The school celebrated its 150th anniversary in 2005 with a visit from one of its old boys, HRH the Prince of

Wales.)

PF’s contributions to Geelong’s extra-curricular activities are recorded in successive issues of The

Corian, the school’s yearbook. As Assistant Scoutmaster, he drove a group of boys to camp and it was recorded that “on

the way those in Mr. Fletcher’s car had an exciting experience, for the car seemed determined to imitate a kangaroo by

bounding through the traffic.” In addition, his Cambridge-acquired rowing skills were not neglected for he coached “novice

rowers on the lagoon”, and had “a crew of boat sloggers if not stylists in the fourths.”

Another talent of which we at the Prince of Wales were unaware manifested itself at Geelong: “The annual

courses of musketry were completed before the term had finished, and owing to the keenness and efficiency of Mr. Fletcher,

we can safely say that more cadets know how to handle a rifle and obtain the best results than ever before in the history

of the school.”

A recruitment notice in The Corian of December 1945 illustrates PF’s lasting regard for Geelong. The

Headmaster of Geelong, J.R. Darling (1930-61), responding to an appeal from PF who had recently taken over at the Prince of

Wales, writes that “he is in urgent need of assistant masters and would like some Old Boys from this School. Details of

what sounds like a fascinating job can be obtained from me.” It would be interesting to know if anyone responded to that

call.

PF returned to Marlborough College, but not for long. Thanks to Terry Rogers, the College

Archivist, we have the following excerpt from the speech given on Prize Day in July 1934 by the Master, George Turner:

"Mr. Fletcher’s appointment here was the last benefit done to the School by Dr. Norwood, my predecessor, and Fletcher was

the first newcomer here to help guide my own trembling hands upon the steering-wheel. It is hard to exaggerate our debt to

him for his untiring and devoted service during the past 8 years - for even when he was temporarily absent in Australia

the inspiration of his work was alive here, as it will be long after he has started his important new work as Second

Master at Cheltenham. We knew we could not keep him long, and though we hoped – as I believe Mr. Fletcher himself

hoped - that he would have time to settle down again at Marlborough, we knew that he was a man destined for bigger work;

and now we must look out for a time when the effect of his stimulating energy spreads beyond the spheres where we knew it

well, the classroom, the Camp, the Club, the rifle range, to that scene of sudden reversals of fortune, the cricket field."

(George Turner became Principal of Makerere College, Uganda, in the late 1930’s. Twenty years after

Mr. Fletcher’s resignation, the super-abundant energy and legendary efficiency of the ubiquitous "P.F." were still

affectionately remembered on a Guest Night in Marlborough College.)

In 1934 at the age of thirty-one, PF became Second Master and Head of Military and Engineering at

Cheltenham College.

(He remained there until 1945, deputizing as Master (headmaster) on more than one occasion. But the top position could

never permanently be his since PF was a graduate in mathematics and Cheltonian tradition required that the permanent Master

of the College be a classicist. Not surprisingly therefore, PF would eventually seek a headmaster’s or principal’s

appointment elsewhere, in Great Britain or in one of the colonies or dominions.)

When we wrote to Cheltenham asking for information about PF’s eleven years at the College, we had a swift reply from Tim Pearce,

Secretary of the Cheltonian Society. Of PF he wrote, “He is actually not as well recognised here today as he should be

and you have prompted me to do something about that. I plan to do a bit of a feature on Philip Fletcher for the next

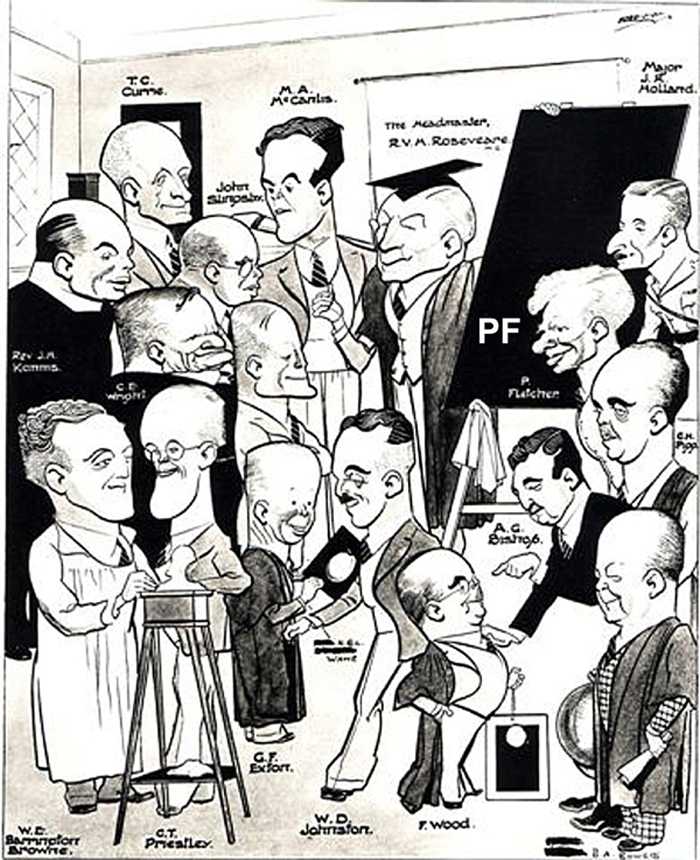

Cheltonian Society News, due out in the autumn.” In the meantime, Tim kindly provided the following cartoon and

valedictory notice. He also provided the portrait photograph of PF lighting his pipe that appears below.

Valedictory Notice from The Cheltonian, Autumn 1945

(Written at the time of PF’s departure for Kenya)

“P.F.! It would be impossible even in several pages to describe or

explain all that these initials have come to mean. Their owner came to us in 1934 to succeed the redoubtable John Mercer

as Head of Military, and his time corresponded with the most critical period through which the College has ever passed.

In times of falling numbers and financial duress, of war and evacuation, of profound reorganization of work and leisure

and feeding, Mr. Fletcher has borne the part of a principal and more than once has had to assume the helm until it is

difficult to imagine the College without him or to picture its life unimbued by his personality, energy and service.

P.F. and other members of the Staff at Cheltenham College

“He has served four Headmasters and done more than any other to initiate three of them. On Mr. Pite’s

tragic death in 1938 – when he had only been here three years himself – he had to take the lead during the interregnum of

that ominous summer term. He rose to the occasion – many who read these words will remember his speech at prize-giving

that year – without realizing for one moment how indispensable he was. That winter Mr. John Bell began his illness, and

once more Mr. Fletcher had to take the reins. The writer will never forget an occasion when Mr. Fletcher visited him to

seek his advice. He had been approached about an important Headmastership and thought it would be inconvenient if he left

Cheltenham. But he genuinely was not sure. It was a startling glimpse into the essential humility of the man.

Fortunately, the answer was clear: it was impossible to contemplate what would happen if P.F. left at that juncture.

And so a good appointment was lost for Cheltenham’s sake and with no suggestion of anything but that it was the most

natural action in the world. At this time in addition to his own work he was acting for the Headmaster in answering

letters, composing reports for Council, interviewing parents and fulfilling the multifarious duties at College House.

“And then came the crisis of the evacuation to Shrewsbury (1938-39, on orders from Whitehall) with Mr.

Bell still far from well. It has often been a matter of remark that at times of critical decision those who have been

expected to be the most levelheaded and reliable fail, and those from whom it would be least expected rise to the occasion

with surprising strength. Mr. Fletcher was neither of these. We expected his strength and it was there. He literally

carried the evacuation on his shoulders. Simultaneously it seemed – an illusion produced by that faithful old car of

his! - he was chief removal contractor and porter of 120 tons of furniture, sorting and packing, at this end, and

unloading at the other – while working out the endless details of timetable and dovetailing with Shrewsbury. At

Shrewsbury he was typically to be found in the most uncomfortable, bleak and desolate billet that he had allotted to

himself in that severe winter which none of us will forget. With equal energy he threw himself into the great return to

Cheltenham in 1940 with its study of central feeding plans and endless committees on all aspects of College life.

P.F., notoriously camera shy, at Cheltenham College, 1934-45

“To those who knew him least his outstanding powers seemed to be those of organization with an exceptional

mind for detail. Those who knew him more found out the spiritual basis of his approach to life and of his teaching – his

powers of sympathy and friendship and wise counsel. The Head of Military had no false dignity and always did all in his

power to lessen any gulf that tended to arise between the older and younger members of the staff. He went out of his way

to motor, walk and talk with newcomers to whom he introduced the joys of the Malvern Hills, Church Stretton, and our local

haunts. There is no need to mention his work in the allotments into which he put the same indefatigable energy which he

had long displayed on the towpath at Tewkesbury. It was the only activity the results of which could be weighed – 99½ tons of potatoes and vegetables in four years. Could more important things be placed on similar scales the total would be equally astonishing. And lastly of his great ability as a teacher some of his old pupils have already written in the letter from Oxford published in our last issue.

“Needless to say, his lightning course upset people at times. Nor was suffering fools gladly his strongest point –

though suffer them he did with infinite patience. Some of us got furious on occasion, yet once, after debating on

how “intolerable’ and “impossible” and “monstrous” some action of his had been, a man ended by saying “But I can’t help

loving the man all the same.” Perhaps that is the truest note on which to end. We all depended on P.F. and we all –

members of Council, staff, boys and old boys – loved him. Cheltenham College once more owes an immense debt to its head

of military.”

(Old Cambrians who served on PF’s Tuesday afternoon work parties at the Prince of Wales School,

having read about the tons of potatoes, will now realize that their burden was light compared to that of their earlier

counterparts at Cheltenham.)

The Prince of Wales School

Main building and Quad in 1932, one year after completion of construction at Kabete

Photograph by H.K. “Pop” Binks of Nairobi. The Prince of Wales School was designed by

Sir Herbert Baker

PF left Cheltenham College in 1945 to become Headmaster at the Prince of Wales School in Kenya. We found

information about his interview and selection in File CO 1045/110 at the Public Records Office in Kew, London, entitled

Vacancy for Headmaster of the Prince of Wales School, Nairobi. If any undeserving candidate thought that during

the last months of the war he could slip into a congenial colonial headmastership, he was doomed to disappointment. The

evidence, sufficiently bulky to require tying up with ribbon, shows that the Colonial Office took this appointment most

seriously; indeed their Education Adviser C. Cox wrote “…we want to get a really first class man with boarding school

experience for the most important European school in British Colonial Africa.”

Applications were invited from local education authorities and public schools in Britain and from the

colonies and dominions including Southern Rhodesia and the Union of South Africa. About twenty strong candidates were

short-listed, of whom three attended a final selection board on 28 March 1945. It is noted that the successful candidate,

Philip Fletcher, had some other “irons in the fire”: he was in the running for the headmastership of Taunton School and of

Upper Canada College, he was also under consideration for the posts of principal of Makerere College, Kampala, and Director

of Education, Nigeria.

Barely legible penciled notes taken during the interview by one of the assessors hint at the Fletcher we knew

at the Prince of Wales:

Self depreciation. Good thinking before he answers on importance of PofW.

Impressive to look at after listening to - weight.

Self confidence over 4 headmasters - experienced & weighty.

Too tense for Kenya? Level headed.

Kept up with Americans or Australians?

Education rooted in religion.

Self-confessed lack of culture. Intellectual stiffness. Trite answers to political or cultural affairs, acute self

criticism.

The final indication of the importance attributed to the post is given by the fact that the Outward Telegram

dated 11th April, 1945 announcing his appointment was addressed to Sir Philip Mitchell, Governor of Kenya, and signed by

the Secretary of State for the Colonies. (The telegram notes that Mr. Bernard Astley, headmaster of the Prince of Wales

School from 1937 to 1945, also interviewed the candidates and thought PF was the most suitable.)

Outward telegram announcing Fletcher’s appointment

(By permission of the National Archives of the UK, ref. CO1045/110)

Returning once again to the 1959 Impala and Vice-Principal ‘Fritz’ Goldsmith’s article, we read that, “Few

people in Kenya realised in 1945 how fortunate the Colony had been to attract a Headmaster of the quality of Mr. Fletcher.

No outstanding Second Master of a famous English Public School, except a bachelor with a previous taste of overseas service

and a strong sense of vocation, was likely to accept the Headship of an obscure colonial school on the Equator, at an

absurdly low salary.

From the 1945 Impala Magazine,

courtesy of the Impala Project and Martin Langley (Nicholson, 1956-61)

“The school to which he came in October 1945 had suffered severe difficulties and setbacks during the

war years, owing to the evacuation to Naivasha, followed by a fantastic growth of numbers and an acute shortage of staff.

During the first five post-war years, the task of working towards high standards in all departments of school life was not

an easy one. Most of the staff were new to Kenya, few had any previous boarding school experience and the turnover of staff

was bewildering: 21 men acted as Housemasters, for example, between 1946 and 1949. The Headmaster's relationship with his

staff was not made easier by the decisiveness, abruptness and avoidance of social intercourse which he practised, in

order to encompass, as he habitually did, the work of three or four ordinary men.

PF on Speech Day, 1954

(Photo supplied by David Stanley, Rhodes, 1949-54)

"No Headmaster could have thrown himself into his task with more selfless devotion. From 7.30 in the

morning, or earlier, till 11 p.m. or midnight or later, with breaks of four or five days each holidays to visit parents

up-country, he worked at the highest pressure to make the Prince of Wales School a happy and friendly school, teeming

with activity in work, games and societies, and one of the best organised in the Commonwealth.”

The high regard in which PF was held by his former colleagues at Marlborough, Cheltenham and elsewhere

greatly enhanced the standing of the Prince of Wales School. As a former pupil from the PF years has discovered, “While

I was at the school, I was under the vague impression that the PoW was a so-called 'Public School' in the English sense,

i.e. an independent school of some weight and reputation. As you probably know, the thing that qualifies an establishment

for membership is whether the existing Heads elect a newly appointed HM as a member of the so-called Head Masters

Conference (HMC). It was rare thing indeed for a Head appointed to an overseas school, and a government one at that,

to be elected. I decided to follow this up and the other day I received an e-mail from the administrative offices of

the HMC which said, ‘Our research has borne fruit. Mr. P. Fletcher was elected into membership on the 16th of May,1946.

He was, at the time, Head of the Prince of Wales School, Nairobi’. I think that is a further mark of the respect in

which he was held by his schoolmaster colleagues at the top of their profession, though perhaps it would have had little

impression on his pupils!” (Nigel J. Brown, Nicholson 1952-57, and Staff 1966-70.)

"In 1948,” as the Goldsmith tribute continues, “there came a crisis over the continued and alarming

increase in numbers, resulting in the Headmaster's dramatic interview with the then Governor, Sir Philip Mitchell, to

insist that a new school must be opened at once. This interview, which brought about the inception of the

Duke of York School (initially) within Government House itself, earned the following tribute from Sir Philip in

his King's Day speech on October 11,1948:

I had one of those painful interviews with Mr. Fletcher with which no doubt most of you are familiar; I had the

slight advantage that it was in my study and not in his, but the result was what you would have expected. It began

by my saying, 'You've got to take another hundred boys next January,’ to which he replied, ' You've got to build a

new school'. I said I couldn't build a new school by the middle of January, and we argued about it and the whole

question quite a bit. But, as I have said, the result was what you would expect, and we have, in fact, decided to

build the new school at once. In this episode between your Headmaster and myself you have an admirable example of

the disciplining of myself by himself. But, joking apart, the episode was in fact an admirable example of that

discipline which enables a man - which, indeed, compels a man - when he sees that a thing is wrong, to go straight

to the highest authority and say, ‘This is wrong and must not be done'. (December 1948 Impala Magazine extract.)

Queen’s Day 1958: PF at attention while Drum Major of the Band, Robin Dine, salutes Lady Mary Baring

(Photograph submitted by Cecil Johnston, Clive 1954-58)

“During Mr. Fletcher's Headmastership, the material appearance as well as the spirit of the school has been

transformed. Among the additions have been the Hawke-Grigg block, the "temporary" School Hall, which for so long served

also as a chapel, the magnificent Swimming Bath, the Squash Rackets court, the new Science Block, the Wood and Metal

Workshops, several new playing fields, including a second Hockey pitch, and finally the School Chapel. The wonderful

response by past and present parents and boys and by friends of the School to the Chapel Appeal, which enabled some

£18,000 to be raised in two years, is perhaps the greatest testimony to Mr. Fletcher's work here. In the Chapel for which

he laboured so tremendously a plaque could well be inscribed with his name and the famous words ‘Si monumentum requiris,

circumspice.’ (If you seek a memorial of him, look around you.)

From the Chapel Appeal Brochure, submitted by Jitze Couperus (Hawke, 1954-60)

The Queen’s Day Report, October 1959

In the second half of 1959, Mr. Fletcher became gravely ill. Fourteen years of Herculean effort had caught

up with him at last and he was burned out. He was only fifty-six, but his time was over. In Fritz Goldsmith’s words,

“PF’s immense industry had a continuous snowball effect on the volume of work which came to him. In striving to cope with

an increasingly heavy burden, he eventually undermined his health. When he went to hospital in October 1959, he was

dangerously ill. The delivery of his long and admirable Report on Queen's Day one week later, straight from his hospital

bed on a diet of a little rice and orangeade, was a remarkable feat and a great ordeal. His steady and surprisingly rapid

return to health was due to what was, for him, the most difficult process of self-discipline: the restriction of his hours

of work to reasonable bounds.”

Michael Saville, Editor of the 1959 Impala, in similar vein notes that “Mr. Fletcher, who had been in the

European Hospital for some weeks previously, was given special permission to be present as it would be his last Queen's

Day as Headmaster before his retirement. He returned to the Hospital immediately afterwards. Mr. Fletcher delivered his

Review of the year's events with his usual penetrating clarity and in a resonant voice: truly, everyone agreed, a tour de

force.”

PF began his speech by extending a cordial welcome to the Distinguished Visitors, parents and friends of

the School, and paid special tribute to Sir Evelyn and Lady Mary Baring who were leaving Kenya after seven years of

service. He then reviewed the prior year’s results in School and Higher School Certificates and took the opportunity to

address one of his enduring hot buttons: “What is quite appalling is the steadily increasing pressure from outside to

prepare boys for Higher Certificate who are completely incapable of profiting by the work, and whose presence in advanced

classes would be a real handicap to the abler boys for whom the classes are rightly designed."

With business matters duly disposed of, PF reflected on his years at the Prince of Wales. In his own

words: “At the end of this term, this great school will have completed the 29th year of its existence, and nearly 3,700

boys will have attended it for periods varying from a few days to 8 years. Over 3,000 boys have already left it, and are

to be found in all corners of the earth. In such a large number, there must inevitably be some tragic failures, some

drifters, some crooks; but I know there is an overwhelming proportion who are giving good service in a very wide range of

occupations.

“I wonder if we all realise how incredibly lucky we are to live in this beautiful place? With all its

faults, inconveniences and inefficiencies, it remains so much more open and spacious than many other schools less fortunately

situated. I understand that there is a strong hope that money can at last be found to replace our temporary boarding blocks

and classrooms by something more substantial, and then we shall be nicer still.

“I wonder if we all realise what happiness and freedom can here be found? This was not always a happy

school; and of course at this or at any other time there are unhappy individuals in it; but for some years now I believe

it has been a school where the vast majority of boys have been happy for the greater part of their time. I should think

something was wrong if all boys were always happy; for school is a training for life, and life is full of rough patches

through which one must live and help others to live. But I do think it tremendously important that there should be an

atmosphere of happiness, confidence, trust, mutual liking and respect and that boys should consciously cherish this and

do their best to maintain and increase it. It has to be constantly worked for - and prayed for - by staff, by prefects,

by boys of all ages and sizes; like all the precious things of life, it can easily be lost. A very great part of this

happiness has been due to the devoted care of Housemasters, and I know that boys and parents share my deep-felt gratitude

to the splendid body of men who have held office as Housemasters.

"It has been my privilege to serve this school for the last 14 of its 29 years of life, and to have had

some responsibility for about 2,800 of all the boys who have attended it. They have been 14 years of great interest and

variety, sometimes pretty hard to live through, often wholly delightful; I would not have missed them for anything, I am

profoundly thankful to have been allowed them, and for all the kindness shown to me by the Education Department and

numberless others.

"I shall be sorry to say goodbye, when the time comes next year; but mixed with sorrow will be no regret

nor grievance, for the load has been becoming too heavy for me.

"It is high time, too, that the school had an entirely fresh and much younger mind brought to bear on it.

A great number of changes are needed, and are overdue; I am sure my successor (Mr. Oliver Wigmore) will make them, and that

parents and staff and boys will welcome them and help their introduction.”

In closing, Mr. Fletcher spoke of the broad challenges faced by his successor: “There are many bulls

whose horns I have not taken: partly through lack of courage, partly through failure to imagine what to do with the bulls

when taken. Here are three, out of many: the priority problem of creating the right curriculum for those who are not

academically minded; the right place of games and such-like in the curriculum as a whole; the need to delegate more to

other people and to keep fewer threads in one pair of hands. Anyone who knows the place well can make a list of a dozen

changes which in due course must be made; good luck to my successor, say I, and to all who serve under him."

1959: a frail PF, battling poor health, poses with School Prefects in his last year.

Prefects, standing from left: John Keaton, John Wyber, Ian Beatty, Peter Sprosson, and Neville Watson.

Seated, from left: Christopher Clark, Brian McIntosh (Head Boy), Andrew Davidson, and Barry Rowe.

Staff Comments in Appreciation of PF

(1959 Impala)

(F.H. Goldsmith) “Some of us will remember PF for his brilliant teaching of Mathematics to forty-odd Fifth

formers in the Lecture Theatre; others for the enthusiasm he could inspire in a reluctant Tuesday afternoon working party.

Many will remember him best for his topical and challenging addresses in Chapel, painstakingly prepared and impressively

delivered. Hundreds of boys will gratefully recall evening interviews in his office, in which their shortcomings or their

future careers were helpfully discussed.

“Some three thousand boys have passed through Mr. Fletcher's hands in Kenya. His labours on behalf of

leavers have been stupendous, and in almost every post there comes a letter to him from a grateful Old Boy in some part of

the world. There is not one of us who has been in close contact with him who has not drawn inspiration from his supreme

efficiency, his understanding of boys, his private generosity, his deep religious conviction and his complete dedication

to his work. On King's Day in 1948 he said 'I look for the day when boys may leave here aflame with the love of God and

Man, seeking nothing for themselves save the opportunity of work to do and strength to do it.' None could have done more

by example and encouragement to achieve that high aim.”

(M.T. Saville) “During my six years as Editor, I have received help in boundless measure from the

Headmaster, who has taught a lesson, not always easy to learn, in that he always takes infinite pains to have every

detail correct down to the last inverted comma: nothing is slip-shod, nothing incorrect and nothing is too much trouble

for him. It was no use to think 'Oh, he won't notice', you soon learned that he would and did - and said so!

“Now it is the Headmaster's turn (to leave school). It is to him, at the end of this term, that our

thoughts turn, and we wish him "God speed, good health". A new decade of the century is almost upon us; Mr. Fletcher will

remember so many endings and so many beginnings. Let us hope this ending, now, will be a happy memory for him. For look!

the sunshine is striking on the beautiful stonework of the new Chapel walls; the breeze is sighing through the gum trees

behind the new Science block, and making ripples across the new swimming pool; the grass on the new playing fields is

drying rapidly. You can see the Aberdares again, today! Remember us, sir, in technicolour, as it were. We know you love

the beauty of Kenya; the loveliness of the setting of this School. And for what you have done, created, worked for,

achieved, with full hearts we say ‘Thank you’.”

The Final Assembly

M.T. Saville writes in the Impala, “Few boys will ever forget Final Assembly in the third term of 1959,

when B. G. McIntosh, the Head of School, made a presentation, on behalf of every boy, to the Headmaster. He spoke briefly,

but sincerely and most appreciatively, of Mr. Fletcher's long and devoted service to this community. The presentation was

a cheque, with which the Head¬master might buy something for his new home, and thereby recall, in his retirement, the

affection felt for him by the boys of this School. The clapping and cheering which greeted this, lasted for so many

minutes, that it was with difficulty, being so moved, that the Headmaster found words to reply. A call by the Head of

School for three cheers for the Headmaster brought a response that could be heard all over the compound.”

Retirement

Appropriately, the last people Philip Fletcher spoke to on Kenya soil were a couple of his old boys, and

it happened quite by chance. Derek Caister (Clive, 1952-57) tells the story: “In 1960, Brian Stacey and I were working in the

East African Customs & Excise Department, attending a passenger ship at the Mombasa Kilindini docks, when we spotted

"Flakey" heading towards the ship. We greeted him at the gangplank, both of us in uniform, Stacey with a full beard and

myself with a moustache. After studying us for a few moments he said, "Caister - Clive House; Stacey - Nicholson!! We

had pre-sailing drinks onboard with him, and that was the last time we saw that truly amazing and dedicated man.”

Mr. Fletcher was on his way home to England to live with his sister at 20 Amberley Road, Rustington, in

Sussex. Once settled, he bought a leather-inlaid desk with the cheque he had received at the final school assembly, and

from it he wrote scores of letters to old boys over the next ten years, demonstrating his famous recall of names, dates,

houses, and talents.

Formal recognition of Philip Fletcher’s career in colonial education came when he was named an Officer of

the Order of the British Empire (OBE) on 11 June 1960. He went to Buckingham Palace to receive the award on 8 November

that same year. The citation, “Headmaster, Prince of Wales School, Nairobi, Kenya” seems pretty thin considering his

charismatic leadership and distinguished service; but maybe everybody knew that just the words “Prince of Wales School”

said it all.

After the UK branch of the Old Cambrian Society was established in 1961, PF became a frequent guest at

its annual dinners in London. Many old boys who were living and studying in Britain visited him at home in Rustington. For

his part, besides keeping touch with his extensive family of Old Cambrians, PF continued to teach part-time.

The final years were spent in a care home. Elizabeth Scoble-Hodgins, daughter of former Prince of Wales

Maths teacher, “Amoeba” Walker, tells us that “Mum and Dad kept in touch with PF in England. There was a period after his

sister died when he was in a very sorry state when Mum would bring his washing home and return it with new replacements.

They visited him regularly when he was admitted to the care home where he sadly died from Parkinson's disease in 1976.”

PF died on February 15th at the age of seventy-two. His funeral took place at Guildford Crematorium in Surrey on February

23rd 1976, and his ashes were buried in the Garden of Remembrance there.

An entry has now been inscribed in the Book of Remembrance held at Guildford Crematorium, on the page for 15th February.

It may also be viewed on line at

www.scribesltd.co.uk/guildford. The wording is as follows:

Philip Fletcher

Died 15 February 1976, aged 72 years

Headmaster of the Prince of Wales School, Nairobi, Kenya 1945-1959

Remembered with Affection and Respect

|

Acknowledgements

The Webmaster and Secretary of the Old Cambrian Society (UK branch), Steve Le Feuvre (Clive 1970-75), together with the editors of this feature,

Brian McIntosh (Rhodes 1953-59) and Christopher Collier-Wright (Hawke 1954-59), gratefully acknowledge the kind

cooperation and valuable assistance provided by:

- Theodore Mallinson of the Foundation Office, Highgate School, and Gordon Tweedale, Director of Art, Highgate School 1973-2005

- The Master and Fellows of St. John’s College, Cambridge, and Jonathan

Harrison, College Librarian

- Mathew T. Reeder of the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library, Princeton University

- Michael Collins Persse, Curator, and Ann Drayton, Geelong Grammar

School, Australia

- Terry Rogers, Archivist of Marlborough College

- Tim Pearce, Secretary of the Cheltonian Society

- Paul Johnson, National Archives Image Library Manager, Kew, Surrey

- Lesley Watling, Ceremonial Secretariat, Cabinet Office, London

- Keith Hendry, Bereavement Services Manager, Guildford Borough

- Old Cambrian contributors living in many parts of the world

Old Cambrian Recollections

(In chronological order by final year of attendance)

Some of these recollections (usually the shorter ones) were taken straight from the alumni section of the Old

Cambrian Society’s website. Some were written specially for this feature, and one is from an Old Boy’s published book.

Additional memories or anecdotes about PF are invited from other Old Cambrians and they should be sent to the Webmaster.

Leonard Gill (Grigg, 1944-48), from his book, Rollicking Recollections, Trafford, 2003

My time at university was not entirely wasted. I returned to Kenya in 1950 at the age of nineteen, a humbled young man,

now more than ready and eager to get down to a job.

Dad had now more or less washed his hands of me. He suggested that I go to see the headmaster of my old

school, the PoW. 'Pink Percy' Fletcher had taken up the job of headmaster of the PoW after the end of WW11, and had

proved to be a dynamic, no-nonsense, professional with a record of having sorted out pretty tough schools in England and

Australia. His nickname came from his florid coloring, resulting from his healthy lifestyle.

I doubt that there was anybody on the planet more suitable for the job he had to do. As students, we

respected him from the moment that he set foot in his office, and we came to admire him as he boldly sorted out problems,

abolished unnecessary rules and restrictions that were difficult to enforce, and were frequently ignored. Pink Percy

inspired self-discipline leading to self-control. He had always regarded me with a jaundiced eye, and rightly suspected

that I was one of the more idle and aimless members of society. But I was sure that he would give me good advice to put

me on an appropriate path.

I approached him with some apprehension. I was going to have to admit to my abysmal failure at

university which would bear out all his opinions of me. I had made an appointment to see him, and he was awaiting my

arrival. He came out to greet me, ushered me into his office, and invited me to sit down. He sat opposite me and opened

with, ‘Hum! Gill. Hopeless at mathematics. What can I do for you?’

I explained my position and my painful failure at Trinity College Dublin. He must have sensed that I was

truly humbled. He seemed to feel that the school had failed me, and that he personally should be held responsible. We

argued this point for a few moments. He had come to the school only shortly before I left. It was hardly fair to hold

him responsible for the years during which I had developed into a feckless lout. We agreed to disagree on this point, and

turned to the question as to what path I should now follow.

He opined that I enter commerce, and should seek employment with a large enterprise which offered

proper training. I applied to an oil company and an import/export firm, and was accepted by the latter. Dalgety & Co. Ltd.

was an Australian firm with an office in the City of London which supervised the East African branches. I'm sure that Pink

Percy had a lot to do with the company accepting me, and I'm sure there was no better organization in which to start my

commercial life.

(If anyone is interested in learning more about Len Gill’s three published books, please contact the Webmaster.)

Paul Heim (Hawke/Scott, 1946-50)

Percy Fletcher was a formative influence on most of us. I remember him as a truly great and good man. He gave the

impression of some slight eccentricity, with his neighing laugh and untidy appearance, but he was a man who knew boys

through and through, and who could bring out the best in each of them. When he thought it was justified, he fought for

them too. What is more - even though he could not have come from a more typical public school background - he was open

minded, tolerant and far-sighted. He was a man of high principles, who made it his business to pass these on. If anyone

knew right from wrong, he did, and he did not hesitate to tell you about the distinction. If necessary, he was ready to

back it by physical punishment. He also tried to teach us to be well behaved in our daily lives. He discouraged profanity

and bad language. I well remember his talk to boys about to leave school, warning them against certain temptations of

which we knew little at the time. His advice to those who were tempted by persons of doubtful character was to raise

one’s hat and say “no thank you, madam”.

One remembers well his tall figure, sparse ginger hair, untidy appearance, commanding presence and

frightening insight. One also remembers his patent love for his school as a unique institution. I think we became

better men because of his influence in our lives.

David Betts (Rhodes, 1948-53)

Today the university system in the United Kingdom, and elsewhere, has become a mass-production industry. Its admission

processes are mechanistic and effected via a computerised conveyor belt. Not so, in the middle of the last century, when

Fletcher was the Headmaster of the Prince of Wales School. Then it all depended on three things: the reputation of one’s

school, the commendation of its Headmaster and finally an adequate Cambridge Higher School Certificate.

Whenever Fletcher went on ‘home’ leave he spent his time and his money traveling to universities

throughout UK to greet and encourage his boys who had become undergraduates, and many of us had the pleasure of meeting

him on these visits. He also took the opportunity to seek out university registrars and admissions tutors and convince

them of the quality of the School’s preparation for university, and of the calibre of the boys he would be recommending to

them.

I discovered this one day at School when I was summoned to see PF. What misdemeanor was I guilty of

this time? None it transpired. He invited me to sit and said that he wanted to discuss my future and suggested that I

had the attributes to consider a career in medicine. He went on to explain that for many years he had maintained a good

rapport with St Thomas’s, a prestigious teaching hospital of the University of London, had sent a succession of boys there

and that they had all been very successful. In 1953 Kester Brown was the only prospective medic in the Biology Sixth Form

and he was aiming to follow his father to St. Andrew’s in Scotland. PF was gently twisting my arm and sent me off to

consider his proposal.

I had visited London during a dreadful winter soon after the end of WW2. The cold, dank smog and

soot-grimed buildings, the austerity and ration-books was a big turn-off and the prospect of five years of it was too

unpleasant to contemplate. So I returned to say to PF ‘thank you but no thank you’. I would prefer to stick to

agriculture, remain in Kenya and go to the then Egerton College of Agriculture at Njoro. I was sure this response would

make him either crestfallen or angry. He was sympathetic and understanding but asked me to raise my sights a little and

consider going to a university in a rural part of England for a degree course in agriculture, and suggested Reading.

After discussing this with my parents I went back to PF to say that this is what I would like to do and to seek his help

in procuring a place for me. To encourage me further he suggested that to feed the hungry and clothe the naked

(nylon was a new expensive novelty and terylene had not been invented) was almost as worthy an occupation as healing the

sick.

Twenty years after that interview I was to join the academic staff at Reading and was able to read what

PF had written about me. He told the absolute truth and did not over-exaggerate one’s predicted CHSC results, but he knew

so much about each of us that he was able to write a very compelling account of whatever talents or strengths a boy might

possess.

(Further to David’s point about PF devoting his time to calling on old boys while on leave in

England, it seems that old boys were equally enthusiastic about trying to see PF. In his 1953 Queen’s Day speech, PF

recalls that on his recent leave one old boy “undertook a journey by three buses and one train, followed by a nine mile

walk, to spend a night at my hotel.”)

Ronald “Rag” Jones (Grigg/Rhodes, 1946-49)

"Rag" Jones has provided a piece of memorabilia, which testifies to Jake's concern for the progress of

his 'old boys':

Jake's reference to 'unduly awkward questions about Latin', had it been delivered to Ron in person, would no doubt

have been accompanied by the trademark, 'hee, hee, hee'.

Roger (Rastus) Bond (Hawke, 1948-53)

Headmaster, 'Vluitjie' Fletcher, also a strict disciplinarian, was a man who had the welfare of the school and its boys close to his heart. Shortly after leaving school, I was in Nakuru hospital after being involved in a car accident. There was a soft knock on the door and who should walk in but 'Vluitjie' just checking on the well being of one of his boys!

You ask whether I can shed any light on the origin of the nickname Vluitjie, or in proper Afrikaans,

Fluitjie. Not a lot I’m afraid, but you will remember that at school a mouth organ was called a 'flakey'. I knew that

this was an abbreviation of the Afrikaans for mouth organ but It wasn't till I came to South Africa that that I learned

how it was spelt in Afrikaans - (mond) fluitjie - pronounced flakey and literally 'a little mouth flute'. In my mind,

PF's nickname was firmly associated with flakey the mouth organ because during the time I was at POW an article appeared

in The Impala containing a cartoon depicting the names of some of the staff. There was a picture of a tortoise

for ‘Mkorbe' Atkinson, a fish for 'Samaki' Salmon, an insect for ‘Dudu’ Knight and a mouth organ for Flakey (Fluitjie).

At a Kenya Regiment lunch in South Africa in March 2005, I managed to track down the person who drew the cartoon. It was

Dennis Field who left school in 1946/7, but the cartoon was not published until December 1948. He confirmed that a mouth

organ was used to depict Fletcher but could not remember any reason why Fletcher was called Fluitjie other than Fluitjie

Fletcher sounded well. Interestingly, several people at the lunch thought that Fluitjie was spelt with a 'V'. Before

talking to Dennis, I had thought that the cartoon might have appeared in The Commentator, a student newsletter edited by a

boy with American roots called Maddox. He was considerably senior to me and was different to rest of us in that he wore a

bow tie!

Ron Bullock (Scott, 1948-53)

I suppose I should say something about Flakey, despite very mixed emotions. It was through Bertie and the choir that I

first came into closer contact with him. Until then I had seen him only as some remote and rather odd character who had a

reputation for not wanting to hear any but religious music and for having an antipathy toward females. I have no idea

whether there was any basis of truth for these stories. Certainly there was one occasion when, passing by, he told the

Scott prefects to turn off their gramophone. We also knew that we could rapidly drive him from the House dance by putting

up one of the girls to go and ask him for a dance. Given these facts, I have sometimes marvelled that his sense of duty,

which so conspicuously deserted him on the dance floor, nevertheless enabled him to deliver, just once to each class in

their school career, and for a full two hours, that excruciating annual sex-education lecture to which we went in such

high anticipation. This he did with a flush to his cheeks and a profusion of snuffles such as I witnessed on no other

occasion – which is saying something.

In the choir he was a perfect menace, everlastingly creeping up behind you and in the most menacing of

whispers, growling with his beery breath, “you’re flat!” or “you’re sharp!” God knows if we were, or whether he really

knew the difference, but it was very intimidating. On another occasion, Flakey stuck his nose into Scott prefects’ study

(or perhaps it was Munya who did this - Mr. Cobb, the Housemaster) and threw open the lockers. Had he been tipped off? In

any event, this exposed the still, which I think Peter Powles was operating, and the fermenting bananas and strawberries.

That caused quite a furor!

I had Flakey for only one term of math. I had been quite good at math up to that point, but alas,

calculus proved my undoing, despite his reputedly good teaching. The one thing I remember from this time, however, was

his rather intriguing approach to problems - “Wouldn’t it be nice if.....” he would say, musing along the blackboard with

his chalk. “Oh but it does!!”

But essentially Flakey was a totally remote being as far as I, at least, was concerned. I remember

only a certain fear, tempered by a certain respect. It was enough and I stayed clear as much as possible. This was not

always easy when you recall that among his more admirable attributes was his ability to recognize and name every boy

in the school within a very short time of their arrival.

And yet, and yet! In my more senior years I came to realize that he was quite approachable if I saw

cause to ask to see him. When I wanted to roam and take the pictures during speech day, which appear on the OC site,

Flakey was wholely supportive - I couldn’t have done it without his prior blessing. I only wish the photos had been

better - or, perhaps, had better withstood the ravages of time. I see that he also noticed Harry Brice’s camera. Not

much escaped him, as everyone has testified. He even rearranged the whole timetable to accommodate my wish to take Maths

with my Arts program on entering the fifth form. It is a pity that my subsequent performance did not justify the

dislocation that must have been caused.

Many remember his great interest in our various sporting activities. I believe it was he who extended

the schools’ sporting competitions to matches against Alliance High School, no doubt in close cooperation with that other

esteemed headmaster, Carey Francis. I well remember his admonitions in assembly before these matches took place regarding

behaviour and courtesy. Remember, I'm talking about the early '50s, with Mau Mau in full swing. Given the attitudes of

many parents at that time, this initiative was surely a brave act on Flakey's part, socially and politically, as well as

an act of leadership. Strangely, I don't remember any matches against Asian schools in my time - perhaps their hockey was

just too formidable!

He was indeed a remarkable man, although to me he remains something of an enigma. I asked to see him

before leaving to make a few comments. I remember observing that I thought it difficult for boys who reached the 6th

with no mark of distinction on their blazer to distinguish them from the meanest rabble! I have dared to assume that it

resulted in the little ‘VI’ which shortly appeared on blazer sleeves, a very sensitive response, I have always thought.

And after I returned from university, he took the initiative in calling me to ask if I would like him to recommend me for

some job or other at the YMCA, who had approached him for recommendations - not what I was looking for, but again, a

reaching out to one of his boys.

And lest you should think that I imagine he left no mark on me, I still carry the memory of one brief

exhortation he made to us in assembly: it should be the goal of every man, he said, to know something about everything

and everything about something. I rather took that to heart.

Peter S. Rodda (Hawke, 1952-54)

I remember 'Flakey' Fletcher giving me six cuts for shooting with a catty at ceramic insulators on some redundant

telegraph posts in the North valley. He was bird watching with binoculars. Thursday afternoons was his time for beating

boys: part of the punishment was having to wait, sometimes for days. He was deadly accurate with the cane, and often one

would see boys cooling their painful posteriors in the washbasins of the toilets just round the corner from his office.

Keith Aikin (Clive, 1954-58): Chairman, Old Cambrian Society (UK) since 1961

I joined the Prince of Wales School in January 1954 after two years at St. Clement Dane’s Grammar School in West London

where I had just been warned by my Headmaster about my lack of academic progress. My previous school turned me off: I was

badly behaved, found the teaching staff uninspiring, and had limited sporting opportunities. I had been disturbed by my

mother’s continuing ill-health and frequent hospitalization. Having been interviewed by Mr. Fletcher, I joined the Second

Year, being placed in Clive House, and started in Intermediate as a boarder.

I think it is true to say that my life was transformed from that moment on: I attribute that

transformation to PF who had created a school in Africa that reflected his vision of what education should be. Not only

had he appointed many outstanding teachers, but he had also provided leadership of the highest quality. He ensured that

there was a caring, pastoral structure in the school, that academic standards were very high, that discipline was firm and

fair, and that there were ample opportunities for pupils to enjoy extra-curricular activities. It was PF who sensitively

broke the news of my mother’s sudden death one Sunday morning during my first term, and it was he who gave me the rock on

which I was able to build my life. The ethos of the Prince of Wales School was so positive, and in my case it provided

the motivation to succeed at school and the inspiration for my future career as a schoolmaster. Philip Fletcher was my

role model.

When I decided to become a schoolmaster after leaving University College, London in 1963, I had PF and

many of the teachers he had brought to the Prince of Wales to thank and to emulate. PF believed in the importance of a

balanced all-round education, which he implemented at the Prince of Wales. This ideal was a major influence on me, both

in my five years at school and in my subsequent thirty-nine years of teaching - including twenty-six as Deputy Headmaster

at King’s Macclesfield.

PF was a tremendous friend, who maintained a keen interest in my future progress. I thought it a fitting

tribute to him when I and a number of other Old Cambrians who were studying in Britain in the early 1960s established a

UK Branch of the Old Cambrian Society which flourishes to this day. We were delighted to have him at our Annual Dinner,

and we were always made very welcome whenever we visited him in his retirement in Rustington. In common with thousands

of Old Cambrians, I owe PF a tremendous debt.

Christopher Collier-Wright (Hawke, 1954-59)

I owe my first encounter with PF to a sin of omission on my French teacher’s part. As form master of 1a, the teacher in

question should have supplied me with books the others already had when I made a late arrival in September 1954.

He didn't do so, and when it was time for afternoon prep in Junior House I didn't have the wherewithal for my devoirs.

Accordingly, I wandered down to the main building and stood under the clock tower, disconsolately looking at the notice

boards. PF chanced across me and was most kind - took me to his office, sat me down in one of his basket chairs (that

astonished me, one never sat in Hazard's study at Pembroke House) and wrote a note to the duty pre in Junior asking him

to help me borrow what I needed. And, next day, my form master duly presented me with my books.

In 1961, seven years after that first encounter, I visited PF in retirement at Rustington on Sea,

Sussex. Perhaps I should say semi-retirement, since he was still teaching some maths at Worthing Grammar School.

Rustington is a calm place of tree-lined roads and detached houses, very much on the Costa Geriatrica. Indeed, my Great

Aunt Jessie, by definition elderly, lived in the next street. Mr. Fletcher had set up home with his spinster sister, of

a similar age, who was serious but kindly, rather austere, and retired after long service - in short, the female

counterpart of her brother. A fine reminder for him of warmer days was a McLellan Sim painting of Mount Kenya; another

was a trickle of Old Cambrian visitors - Charles Howie and Peter Sprosson had been there the previous week.

Later on, I think in 1970, I had a round robin letter from PF, addressed to many OCs and written in a

care home. He remarked on the fact that four meals were squeezed between nine and six, and commented, in saucier vein

than one normally associated with him, on the curvaceous young staff.

That was the last I heard. Philip Fletcher died on February 15th 1976. It’s a pity I didn't seek him

out again, but I was overseas most of the time and preoccupied with a young family.

Dave Burn (Scott, 1955-59)

The following quote appeared in the East African Standard when Jake’s retirement was announced in 1959. It comes

from a speech he made a few years earlier, and it sums up his philosophy of what a schoolmaster’s job is all about:

“(It is) to help each boy develop to the full all the powers latent in him - powers of spirit, of mind and body;

to encourage in him self-discipline, sympathy, understanding, tolerance, reasonableness; to kindle, if it is possible,

interest in religion, art, music and good literature; to develop toughness of fibre, ability to stand up to hardship and

hard work, moral courage to stand up for the right – in a word, to help him to become a worthwhile citizen of the Kingdom

of Heaven and of the world.”

Brian McIntosh (Rhodes, 1953-59)

In his prime, Philip Fletcher was a big, well-built man with a commanding presence. His hair was sparse and gingery, his

complexion pink, and his attire rumpled. He was a confirmed bachelor and a loner who didn’t socialize with the staff or

anyone else, and he had no life outside of his position at school. He spoke with a pukkah accent, punctuating his words

with outbursts of gleeful laughter, and he walked at a near-run with a fluid, gliding motion that enabled him to swoop

down unexpectedly on whomever he wished to address. (Some described the Headmaster’s mirth as knowingly evil - the kind

that comes from one who has seen and done every schoolboy trick in the book.)

Mr. Fletcher was a nature lover, a bird watcher, and a mountain climber who once walked right across

Tasmania. This love of walking continued throughout his time at the Prince of Wales: up and down St. Austin’s Hill he

strode, and late at night he prowled the compound on foot, causing dismay among returning truants, midnight smokers, and,

during the holidays, teenage couples car-parked by the pool. To describe him as ubiquitous barely does justice to his

uncanny knack of popping up just when one was bending a rule – or simply contemplating doing so.

The Headmaster’s spirituality and religious faith were profound, as witnessed by his passionate drive to

raise funds for the School chapel, the rigorous devotional schedule he set at Easter 1959 in the new facility, and his

love of solemn hymns like Wesley’s, Jesu, Lover of my Soul. Ever concerned for moral fibre, he was known to stop a

boy in the hallway and, out of the blue, ask how he was doing in the fight against self-abuse.

While in private he was called Flakey or Jake for his idiosyncrasies, he always commanded high respect.

He could be alarmingly severe when angry or disappointed, and he was a stiff disciplinarian. At the same time, as these

Old Cambrian Recollections show, he had a sense of humour, and he could show great sensitivity and understanding. Mr.

Fletcher was never ‘popular’ the way a Bertie Lockhart, an Alan Potter, or a Teddy Boase was, but a majority of the lads

admired him and felt an affectionate appreciation for his flakey ways.

My own relationship with him over nineteen terms was positive. It began rather badly, however, when he

took me to task over an incident in class: a steamy (for 1953) Mickey Spillane novel was making the rounds and I was the

one who got caught with it. A year or so later, he told my parents that I wasn’t academically inclined, but I

surprised everyone by being a late bloomer and scoring well in School and Higher School Certificates before going on to

university in Scotland.

As a school prefect I came to know him a little better, and on one occasion I got a rare glimpse of his

bachelor quarters when he invited six or seven of us to tea. The décor was spartan, to say the least, but mounted on the

wall above his mantelpiece was an impressive set of varnished oars inscribed with the names of his fellow crew members.

Below them sat a display of silver cups, framed pictures, and other memorabilia of his rowing days at Cambridge.

Another vivid memory is that of the House dances in 1959 when our guests were girls from the Boma

(Kenya Girls High School). Protocol demanded that Mr. Fletcher entertain Miss Stott, his opposite number, for dinner,

and so he gallantly donned an ancient tuxedo by then several sizes too small. I saw him during the evening when he made

a late appearance at the Rhodes House dance. His cheery smile and slight buzz had me wondering if he’d taken a few

drams to fortify himself for an evening with the redoubtable Miss Stott.

When Mr. Fletcher spoke to sixth form leavers in 1959, he urged us to avoid debt and wicked women, and

he said we should learn how to cook. At the time, I thought the bit about cooking was silly; within a year or two of

leaving school I realized it was eminently sensible.

We Old Cambrians who knew him well are now in our sixties and seventies, and we feel a keen sense of

nostalgia for those ‘salad days’ when we were young and ‘green in judgment’. Can it be that the passing years have made

us even fonder of the man today than we were a half-century ago? One thing is for sure: we were indeed fortunate and

privileged to have attended the Prince of Wales School in the time of Philip Fletcher.

John Davis (Grigg, 1956-60)

I went through school recognising that Mr. Fletcher was special in many ways but it is not until later when you have been

though life's experiences that you realize just how special. I remember his farewell function and the rousing send off

and the way the sleeves of his slightly untucked shirt were always half rolled up. I also recall his sex talk to us young

rabble in the lecture room under the clock tower and walking up the quad afterwards saying to a colleague, 'but I still

don't know what to do!' The way he used to sing hymns always fascinated me - he seemed to be slightly out of phase with

the rest of us. Also I have a special memory of him teaching me maths in the 5th Form - which effectively sealed my

love of the subject and proved very useful in my subsequent civil engineering life at university and afterwards.

Rev. Harry J. Brice (Rhodes, 1955-60)

Four weeks after I arrived at school I had my first opportunity to meet with the Headmaster. My parents and the girls were

due to arrive by plane at Eastleigh, and I’d been given special permission to go and meet them. While I waited to be

picked up near the main school tower, Mr. Fletcher came over to me, called me by my name and went on to

comment about what I had been up to in my first few weeks, asking, “We have a new photographer do we, Harry?” I was one

of four hundred new students, and he knew me by name. I was not the new school photographer; I was just a first year

rabble with a brownie box camera around my neck. I was impressed. As the years went by, I came to know him as a great

man, who stood up for his students.

Jeremy Whitehead (Clive, 1958-62)

I can recall attending the first assembly of a new term and listening to the headmaster, Fletcher, lecturing us on

appalling behaviour on the school train to Uganda at the end of the previous term. He was unwise enough to describe one

particular event when a group of us had set upon a St Mary's boy and hung him out of the train window by his feet,

whereupon the whole school erupted in a great gale of laughter bringing the lecture to an end as he (Mr. Fletcher)

was unable to prevent himself joining in the laughter.

*******

Additional Old Cambrian Memories and Comments

(In chronological order by final year of attendance)

Webmaster’s note: the following recollections and comments were submitted (or found in the alumni section) after

the Fletcher appreciation first appeared on the Society’s website. Additional contributions are invited from Old

Cambrians, including former Staff members and their families.

Alumni Biography extract from Raymond Birch (Hawke/Grigg 1942-46)

Discipline was harsh at the School and could not possibly survive today. I don't think it did me any harm though and I had

no reservations about sending my own children to boarding school albeit not the PoW. I realize now that Percy Fletcher

was an inspired Headmaster and I attribute to him much of what I achieved in adulthood.

Robert Stocker (Hawke/Nicholson, 1943-46)

When Burbley (Bernard Astley) retired, Bush was Headmaster for one term, and then 'Flakey' Fletcher took over. The older

boys found Flakey was not strict enough, being used to Burbley. Flaky was only Head for one term before I left. He wanted

to talk to my mother about my future. He said, “I do not know what to suggest for Robert, I can just see him on a cattle

ranch throwing steers on the ground and branding them”. My mother was not amused. Flakey had been teaching in Australia.

(The closest Robert came to fulfilling PF's vision for him was when he joined the East African Tanning Company in

Eldoret in 1947. 'Robert Stocker's Memoirs' in the OC Alumni section are well worth a read.)

Alumni Biography Extract from Rob Ryan (Hawke, 1945-50)

Fletcher was a bit of a change from 'Bushbaby' (Forest) who had held the fort during the war years. Cambridge rowing blue

and a way with the cane that was impressive, he towered above us and had an evil knowing grin that told you that he could

see right through you and read all of your inner secrets. He was a bloody good Head.

W.N. Stephen, (Rhodes 1946-51)

Foremost in my memories of those years was the enormous respect I developed for our Headmaster, P. Fletcher, a respect that

grew in later years when I learnt of the generous assistance he gave to promising school leavers. I also have a vivid

memory of walking down from Rhodes to the classrooms on crisp clear mornings and seeing the peaks of Mount Kenya almost

close enough to reach out and touch.

Ron Bullock (Scott, 1948-53)

Brian and Christopher - I'm sure you are well pleased with the piece - you

did a great job. So much about Flakey that I never knew. I think I mentioned that my brother in law had been a teacher at

Cheltenham in the 70s. Strangely, he was a Cambridge man, ran the CCF and coached rowing; but he was languages,

not math.

Derek Woolfall (Scott, 1948-53)

I just happened to browse the web (having tired of working) at the office,

and saw the tribute to PF. It is great, and I wish my memory was better! Also noted that Ron Bullock said he didn't

see any sports with the Asian schools. I

seem to recall that the PoW played hockey (field) against the Asians, and we

also had 'triangular' athletic meets, where the African scored twice as many

points as us, and we scored twice as many as the Asians!. About the only

item I recall is that I once got caned by PF for not locking my bike in the

rack on the North side of the main building (I was a day boy at the time). Good job to all contributors.

Alumni Biography extract from Anthony Sheridan (Clive 1949-54)

Among my memories of school is one of Flakey standing outside his office, tie askew, shirt collar curled up at the points,

smoking his pipe and staring intently at me [and all others] that passed at the end of morning school. He always made me

feel guilty, usually for good reason.

Ellis Hughes (Nicholson, 1952-55)

I enjoyed very much the article on Flakey; he used to scare the hell out of

me at times although I only got one beating from him. And I know he was

instrumental in getting me into the Camborne School of Mines, UK. (In his vivid alumni page entry on the website, Ellis

offers the following additional comment.) In the article, there is mention of PF’s fast walk. With the black cape or

whatever it is called he looked like the avenging angel come to visit. I never, not ever, saw anyone try to put one over

him or even argue; frightening chap really until one knew him better, and by then usually too late.

Colin Dyack (Grigg, 1949-55)

The only staff name that could strike terror was "Flakey" – especially when he was on your trail. When it all ended in

his study, he had a big smile and said, "I'm going to beat you. Heh, heh, heh!" It wasn't too bad and I always got a

handshake and his usual saying of 'Well stood, Dyack". That meant I didn't flinch or cry. Empire stuff!

Ewart Walker (Nicholson, 1951-55)

On the question of PF's name, while I have vague memories that it was Philip, as far as I can remember boys in my day called him either Percy or Vleikie. Vleikie, or Vluitjie as it is noted in other PF notes (see Roger Bond above), meant a mouthorgan in Afrikaans, and I believe it arose from his somewhat inane grin revealing a row of imperfect teeth that looked like a mouthorgan.

Also, in notes elsewhere where his slightly evil laugh is said to have been a "heh, heh, heh", to me it was always "hee, hee hee." Sorry to be pedantic!

I think we were all pretty terrified of Vleikie and I well remember Saturday mornings when the whole school gathered in the main quad and then marched down to the new assembly hall via the steps in the main entrance . Vleikie would stand there and pick out two (or was it four) unfortunate lads to read a lesson the next week in assembly. We all hoped against hope we wouldn't be picked and tried not to look in Vleikie's direction as we went down those steps. **

Vleikie's lack of clothes sense is of course well documented, and I well remember being unlucky enough to sit in the front row of the lecture theatre and see at close quarters the egg stains on his tie .

But he was a great man for all of that, not least as demonstrated by the fact that when the ship that was carrying him to a well earned retirement in 1960 stopped in Dar es Salaam, Vleikie went out of his way to visit my father and see how his old pupils, we two Walker boys, were getting on.

** Brian McIntosh (Rhodes, 1953-59) writes, "I agree completely with Ewart about the terror of having to read the lesson. When it was your turn to stand up there on the stage, without a lectern, in front of five hundred or more sniggering critics, the audience could tell you were weak-kneed with nervousness because the ends of your khaki shorts would quiver."

Peter Dodd (Nicholson, 1950-56)

I remember Flakey (I thought it was because of his skin, which flaked) one time when Assembly was very rowdy and really